The Pulham Family - Cement Artists

Introduction

John Lockwood had a long established a building firm in Woodbridge when, in 1802, he formed a partnership with his nephew William Lockwood. Four years later William built himself a imposing house which was clad in cement and colour washed to make it look like stone. He went on use this process, known as stuccoing, on other houses he built in Woodbridge. These houses also had decorative features, such as porticos, entablatures and key stones, which were made by pouring liquid cement into wooden moulds.

John Lockwood retired in 1815 and William became the sole owner of the company. Two years later he had perfected a method of making cement which looked like Portland stone without being colour washed. William soon had teams of men working on a number of sites outside Woodbridge. All the decorative features required were cast in cement using moulds made by James and Obadiah Pulham.

James Pulham had been taken on as an apprentice by John Lockwood in around 1800 James was the eldest of ten children of a poor family who lived on what is now Cumberland Street. Some time later his younger brother Obadiah joined the firm. James had not received any formal education but he made up for this by attending evening classes and, as soon as his apprenticeship was finished, he was appointed foreman of the thirty strong workforce.

Sometime between 1819 and 1822 Lockwood opened an office at Spitalfields, not far from Liverpool Street Station. James Pulham was installed as manager and his brother Obadiah as assistant. The business moved to larger premises at Tottenham in 1825 but only 9 years later it closed because of increasing competition from other builders who by then had access to cement that was as good, or better, than Lockwood's.

The Pulhams decided to stay in Tottenham and proceeded to build up their own business for decorative cement work. Their only documented project during this period that was the building of a large Norman-style folly at Benington Lordship, near Stevenage in Hertfordshire. The designer was probably Thomas Smith, an eminent architect and the County Surveyor of both Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

In 1838, not long after the completion of the folly, James died suddenly aged 42. He left a widow, Mary Anne and four children. It is not known where he was buried. This has led some to suggest that his early death was due to suicide. His eldest son, another James, who was only eighteen years old at the time, took over the business and his son and grandsons also eventually joined him.

The Pulham’s mastery of making decorative objects in cement was inherited by James II who decided to concentrate on creating picturesque rock gardens using artificial rocks made from cement. He and two further generations of the family went on to achieve a national reputation for their landscape gardening and for their production of garden ornaments in artificial stone.

For the first few years James II worked with his uncle, Obadiah. In 1842 they moved the business to Hoddesdon, in Hertfordshire where they had a number of influential contacts. One of these was John Warner, for whom they landscaped a large garden in the grounds of his house. The major features of this garden were the lakes, cascades and fountains amid clusters of both natural and artificial rocks.

Their next garden assignment was for William Baker, at Bayfordbury, near Hertford, where they built a rock garden, and later returned to build a grotto and further rockworks on the estate.

Both of these gardens have since been completely redeveloped, so the earliest surviving Pulham garden is the one for Thomas Gambier Parry, the fresco painter and philanthropist. He was impressed by the Pulham’s work at Bayfordbury and asked them to work on his garden at Highnam Court, Gloucester.

At Highnam Court the Pulhams were asked to install a sample piece before they were awarded the contract to proceed with the major garden construction. The sample piece, a classical statue on an ornate plinth, was made of cement. This being acceptable they then laid out a formal garden, called the Ladies’ Walk, in which all the statutes, ornaments, pillars and balustrades are made of cement. The Ladies’ Walk leads to the Owl Grotto constructed from stones made out of cement. Beyond that there is a large expanse of lawn dominated by an large outcrop of artificial rocks made out of cement.

A comprehensive set of photographs of the Pulham’s work at Highnam Court and at other gardens and parks around the country can be found at www.pulham.org.uk.

The Pulhams created artificial rocks and stones, which James II eventually called ‘Pulhamite’, by assembling a mass of clinker and other discarded building materials to form the rough shape, and then coating it with Lockwood’s Portland Stone cement. The key to there craftsmanship was the way in which they were able to simulate the surface of natural rock.

James II eventually started to produce his own cement, probably based on Lockwood’s formulation but, during the 1870s, he switched to using mass produced Portland cement.

It would appear that Obadiah Pulham was not particularly interested in his nephew's diversion into landscape gardening, because he left to become Clerk of Works on a number of church-building projects for Thomas Smith. Eventually he retired to Woodbridge where he died in 1880.

The sample piece made to secure the contract at Highnam Court. The classical statue and its ornate plinth were both made of cement.

This rock feature at Highnam Court is believed to be the earliest example of 'Pulhamite'.

The 'Ladies' Walk' at Highnam Court.

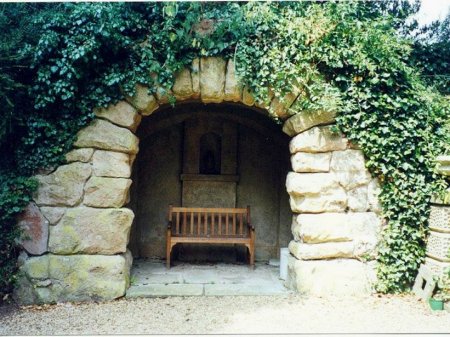

The 'Owl Grotto' at Highnam Court.

Business Moves to Broxbourne

During the mid 1840s James II moved the business a mile or two south from Hoddesdon to Broxbourne, where he bought land near the newly built railway station. He had ‘Pulham House’ erected for himself and his family and behind it there was a kiln, a grinding machine and workshops. These facilities enabled him to increase the production of both cement based garden ornaments and clay based ones. The latter were in two colours - buff and a terracotta red. All three types were called Pulhamite stone. Having the site near a station made the transport of goods easier.

The works closed in 1945 and in 1966 the house was demolished to make way for a station car park and a housing estate. The kiln and grinding machine were left untouched to mark the presence on an important industry.

Pulham House at Broxbourne before its demolition.

The remains of the grinding machine.

The remains of the kiln.

To produce the clay based ornaments pieces of claystone were ground to a powder. This was fed into the moulds used to make a wide range of garden ornaments - vases, fountains, balustrades etc. - which were eventually fired in a kiln.

One of their earliest examples of the terracotta ware was a pale red, richly ornamental vase of intricate design made for the Great Exhibition of 1851. It won a prize medal.

The vase which won prize medal at

the Great Exhibition of 1851

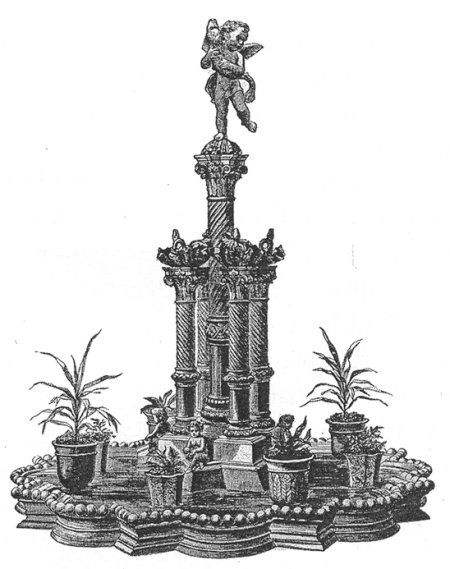

The inspiration for the designs and shapes of their vases was mostly contemporary; a Victorian mixture of Classical and Gothic. The work of famous sculptors provided patterns for figures on fountains such as the one shown below. Pulham submitted it to the 1862 International Exhibition in London. 'Not too large for a moderately-sized conservatory', it was commended for its architectural decorations and sound and durable material.

The exterior fountain above was made from cement.

This drawing is of fountain for a conservatory.

One of these fountains was submitted to the

1862 International Exhibition in London.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries a number of other manufacturers started to produce artificial stone ornaments. The best known being Mrs Coade, Blashfield and Doulton. The art critics approved of their products because they had been calling for ‘artistic common things, and useful artistic things’ and the customers certainly agreed. There was an increasing number of wealthy industrialists and others all over the country with money to spend on beautifying their gardens and artificial stone was considerably cheaper than marble or real stone.

In 1865 James II was joined by his twenty year old son, James III, and the firm henceforth became Pulham & Son. By then their manufacture of terracotta had been considerably expanded and their wares were well represented at the Paris Exhibition of 1867.

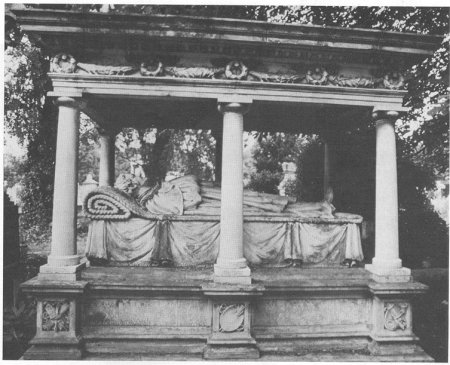

Their chief exhibit was a monument built for the Science and Art Department of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) to mark the death of the painter William Mulready. It incorporated a life-size effigy resting upon a raised bier and supported by a square pedestal around which were bas-reliefs illustrating some of Mulready's principal pictures. Resting on the pedestal were six columns supporting a canopy.

The monument was sent to Paris on the recommendation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and was awarded a silver medal. On return from Paris it was erected over Mulready's grave at Kensal Green Cemetery where it remains today.

The monument to William Mulready which now stands in Kensal Green Cemetery.

By 1865 the firm of Pulham and Son was also building rock gardens and ferneries all over the country using both their artificial stone and natural stone when available. In 1868 work began on a series of waterfalls, a rocky stream and a cave to serve as a boathouse at Sandringham. The cliff at Bawdsey Manor is the only local example of their work during this period. It has grottoes, seats, pathways and rockeries and is finished off with thousands of tiny shells which glitter and shine in the sunlight.

In 1877 the firm produced a comprehensive promotional booklet entitled 'Picturesque Ferneries and Rock Garden Scenery' in which they extolled the natural beauty of their creations and gave a list of their 150 'satisfied clients' some as prestigious as the Prince of Wales, Henry Bessemer and the Marquis of Westminster. They appended a list of the ferns and alpine plants that they recommended for use in these environments.

The firm opened a London office in Marylebone Road in about 1883 and later moved it to Finsbury Square. James II went to live in Tottenham at about that time, leaving James III to take over the house and manufactory at Broxbourne. It is believed that from this time James II concentrated on the marketing aspects of the business, and left his son to manage production.

A Pulham fernery at Dewstow

The boathouse at Sandringham.

Not all of Pulham’s rockwork was for private individuals. The early nineteenth century saw the movement for public parks as places for exercise and refreshment in the cities.

Battersea Park is the most well-known of those in which the firm was involved. To screen the view of Clapham Railway Station from the lake, huge artificial rocks were piled up on level ground to create a mountainous scene, complete with waterfall and a stream.

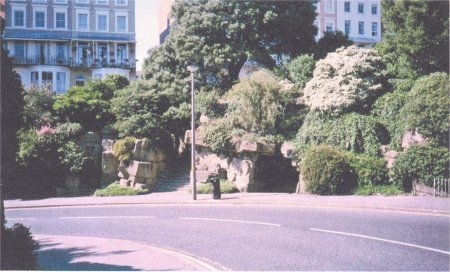

At Preston they built rocks and waterfalls. At Ramsgate, in the last decade of the nineteenth century, they were contracted by the local authorities to build rockwork gardens to attract summer visitors, while at Folkestone huge cliff walls were built either side of an existing coastal path.

Pulham's rocks were not just thrown together. Not only was the base material thoroughly covered, but the surface was fingered, tooled and brushed to make the finished effect more convincing. 'Rocks' were spectacularly tilted to imitate geological faults; streams were diverted, ponds drained and water fed through cemented trenches to feed cascades and water gardens. The greatest possible care was always taken to ensure that their rock structures blended, almost blissfully, into its natural surroundings.

James II said that it was reading Phillip’s Geology and Glimpses of the Ancient Earth that gave him his love of geology and led him to making his 'rocks'.

Of one garden it was said 'that it is difficult to believe that man has had any hand in its arrangement and construction.' Even some experts were taken in. Sir Robert Murchison, an eminent naturalist, was deceived by the rocks at Lockinge (Berkshire) and declared them to be of the same stone as the local church.

From the 1880’s, when the fashion for rockeries and ferneries was beginning to exhaust itself the Pulhams were building water gardens and designing Italianate features and fashionable garden furniture.

James II died in 1898 at his home in Tottenham but he was buried in Broxbourne churchyard. Some three years earlier the firm had been granted the Royal Warrant for work carried out at Sandringham and later at Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace. By this time the firm was in the hands of his son, James III and his grandson, James IV.

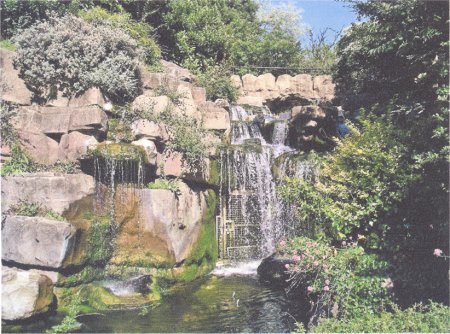

Madeira Walk, Ramsgate

Waterfall, rocks and pool at Madeira Walk, Ramsgate.

During the early years of the twentieth century James IV’s younger brothers Frederick, Sydney and Herbert also joined the company. Herbert established nurseries at Bishop Storford to produce the plants and shrubs for the firm’s rock gardens.

In 1912 Pulham and Sons built a rock garden of natural Sussex sandstone into a north-facing hillside at the RHS Garden at Wisley. Some modifications and improvements have taken place since but it is still a most striking feature of the gardens.

James III retired and died in 1920. The fortunes of the firm declined steadily until trading ceased during the early years of the Second World War. The staff needed to look after huge gardens did not exist anymore and years of austerity spelled the end of lavish expense on horticultural fashions.

James IV died in 1957, and nine years later the family house and manufactory were demolished to make way for a new station car park. During the 1980’s most of the rest of the site was used for housing but the kiln and the grinding wheel remain and there is a plaque – fittingly in terracotta - recording the history of the site.

The greatest monument to the Pulhams is their work in gardens and parks around the country. Given the durability of the materials and the thoroughness of the execution there are likely to be more examples of Pulham rockwork and terracotta ornaments waiting to be discovered beneath the overgrown foliage.

The only surviving catalogue of the wares of Pulham and Son is circa 1920. By then their range had expanded. In addition to vases and fountains there were seats, balustrades, sundials, bird baths and pergolas. Unfortunately not all the firm’s items were stamped and, in the absence of any earlier catalogues, it is difficult to be certain about the provenance of any item that is sold as Pulhamite today.

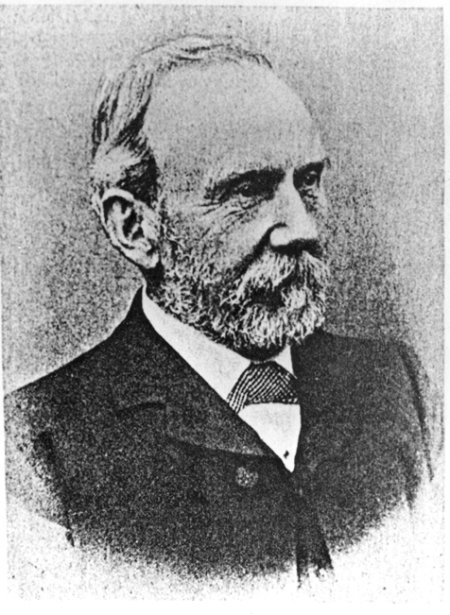

James IV

Woodbridge in the Olden Times, William Lockwood.

Memories of AG Lockwood and Co, West Gate-on-Sea, Queenie Johnson, Margate Civic Society Newsletter 2006.

The Pulham Family of Hertfordshire and their Work, Kate Banister, Hertfordshire Garden History: A miscellany, Ed Anne Rowe.

Durability Guaranteed. Pulhamite Rockwork - Its Conservation and Repair, English Heritage Publication No 51339.

Last edited 19 Aug 23