Thomas Churchyard - Landscape Painter and Lawyer

Thomas Churchyard (1798-1869) was regarded as a liberal and learned advocate at the Suffolk assizes. He was also a talented amateur artist who took every opportunity to paint and sketch in Woodbridge and the surrounding countryside. Today is he is recognised as an accomplished landscape painter.

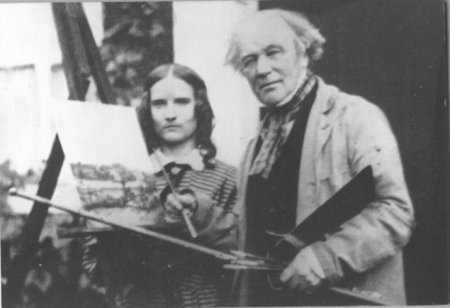

Thomas Churchyard and Laura, one

of his five daughters, circa 1860

Thomas Churchyard’s paternal ancestors were yeoman farmers in the Framlingham area. His grandfather increased the family’s wealth by moving to Melton and setting up a butchers shop, a slaughterhouse and a tannery. He also became a cattle dealer and, every fortnight, he drove pigs from Melton to Smithfield Market in London. His business prospered even more so when he was appointed purveyor of meat to the nearby workhouse of the parishes of the Loes and the Wilford Hundreds.

Thomas Churchyard’s father took over the family business in 1804 when his grandfather and two uncles decided to concentrate on farming. A third uncle joined a bank in London.

Thomas Churchyard’s mother, Alice, was the daughter of Thomas White, a wealthy grocer and draper from Peasenhall, Suffolk. The marriage raised the social status of the Churchyard family and brought a sizable dowry.

Thomas Churchyard, an only child, was born at Melton in 1798. From aged 10 to 18 he was a boarder at the grammar school at Dedham., then the leading school in East Anglia. His father, anxious for his son to pursue a professional career, articled him to a firm of solicitors in Halesworth. This was followed by a year in London during which he inherited £100 from his grandfather.

At that time most newly graduated attorneys gained their first appointment by marriage into a legal family. Churchyard could have advanced his professional prospects in this way in Halesworth. When he left aged 22 there was a bevy of eligible attorney’s daughters then unwed. He chose instead to return home and join the practice of James Pulham who had offices at the eastern end of the Thoroughfare. Pulham did not have the highest reputation so it is possible that they both earned most of their living by defending the less well off in court.

In 1825, Churchyard married Harriet Hales the daughter of a naval Lieutenant. They set up home in a rented house in 29 Well Street (now Seckford Street). Only two months later Thomas, their first child, who was always known as Tom, was born. Their next child, Ellen, arrived in 1826. She was the first of seven daughters. The others were Emma (1828), Laura (1830), Anna (1832), Elizabeth (1834), Harriet, (1836) and Kate (1839). The family was completed in 1841 with the birth of their second son Charles - known as Charley.

In 1825 Churchyard’s father died. He left his house and its contents to his wife. The rest of his personal estate was converted to money and equally divided between his wife and son. Four years later one of Churchyard’s uncles died. He had become chief clerk at a bank in London and had invested in land in the neighbourhood of Woodbridge. This land, and a substantial amount of money, was bequeathed to his brothers and sisters. Thomas Churchyard received £500 and a further £500 was invested for his son Tom.

Thomas Churchyard at 29 Well Street.

(Possibly a self portrait. If not it was

probably painted by George Rowe)

Harriet Churchyard at 29 Well Street

Churchyard probably never had any formal training as an artist. It seems likely that he refined his skills by sketching and painting in the company of other landscape artists in the neighbourhood – Henry Bright, Daniel and Brook Hart, Charles Kell, Perry Nursey, John Moore and George Rowe.

Like many self taught artists Churchyard also faithfully copied the works of established painters until he mastered the technique and style they employed. Throughout his life Churchyard eagerly collected and copied paintings by his favourite artist John Crome of Norwich. The second major influence on his own work was John Constable whose paintings found a treasured place in the Churchyard collection.

In 1829 Churchyard exhibited at the Norwich Society of Artists’ exhibition and was duly elected an honorary member. In 1830 he exhibited at the Society of British Artists and, in the following year, at the Royal Academy.

In 1832, after ten years as a lawyer in the town, Churchyard decided to sell up his house and possessions and to try and establish himself as a professional artist in London. It is not known whether he had long harboured such an ambition or whether it was a reaction to the three bequests he received during the period 1825 to 1829. His wife, and their four young children, went to live with his widowed mother in Melton.

When Churchyard left Woodbridge for London he was accompanied by his friend George Rowe. While there they met to paint regularly but they did not share a studio. Little is known about what they did to establish their names. Churchyard submitted landscapes to the Royal Academy in 1832 and 1833 but they were rejected by the Selecting Council. After only 18 months Churchyard and Rowe returned to Woodbridge.

Others they knew also found that conditions were hard for landscape painters. Perry Nursey who, like Churchyard, had given up a learned profession to try and make a career as an artist, but he failed and instead turned to architecture. While in Norwich John Berney Crome was in financial problems.

On his return from London Churchyard rejoined his family and moved them into rented accommodation, The Beeches, at Melton. To re-establish himself as an attorney, he had a makeshift office adjoining a coal and corn merchant's premises in Quay Lane. During his time in London the Game Laws had been altered root and branch. The new laws were complicated in the extreme but he soon mastered them. He became renowned for being able to expose the most unexpected defect in an indictment, and to display every fact in a light favourable to his clients case. The historian Glyde wrote that ‘Churchyard so frequently defended in poaching cases that he became known as the Poacher's Lawyer. He was so well acquainted with the law relating to game offences that he was dangerous in a bad case and irresistible in a good one’.

Churchyard was eventually able to move his office from Quay Lane by entering into partnership with a young attorney Edwin Church Everitt. He had recently qualified and had opened an office on The Thoroughfare. Before a year passed, the growing practice of Churchyard and Everitt needed more ample accommodation. This problem was solved by moving to Marston House in Cumberland Street. Everitt lived there and part of it was set aside as their law office.

In about 1837 the firm of Churchyard and Everitt was joined by Daniel Charles. His sister was married to a member of the Meadows – a distinguished family in the area. In deference to David Charles' standing, the partnership was styled Churchyard, Meadows and Everitt. With three partners, Everitt's house in Cumberland Street was unable to provide adequate accommodation and a second office was opened on Market Hill.

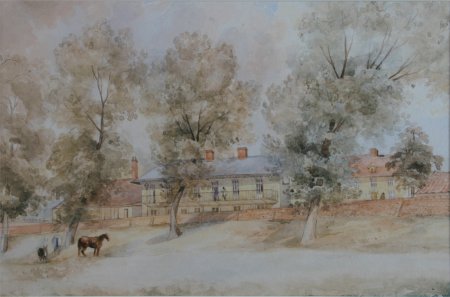

Everitt was first to leave the partnership. He left it in September 1841 and went to Great Yarmouth. Churchyard then took over Marston House thereby giving himself an office and a family home under the same roof. It was a splendid Georgian red-brick building of five bays, three stories high and with the most elegant door case in the town. The Churchyard’s last child, Charles had just been born. Their seven daughters were still at home and were being educated by Ann Bird a resident governess aged 20. Their eldest son, Tom, was away at boarding school. To serve the household there were two female servants.

In 1843 Churchyard’s mother died and he inherited all her capital and her two properties in Melton. A year later his wife inherited from her mother. This inheritance enabled the girls to be educated in a manner befitting the daughters of Woodbridge's liveliest attorney. In the first week of August Ellen, Emma and, presumably, Laura were dispatched to a boarding academy in Bury St Edmunds.

Marston House Cumberland Street

During the same year the partnership with Daniel Charles was dissolved and Churchyard was practising on his own again and this was the case for the rest of his life. Advocacy brought him into court far more often than any other Woodbridge lawyer. How much of his time he gave to the traditional work of a small town, family solicitor is not known. He certainly kept himself free of any standing appointments that carried with them routine commitments. This gave him amble opportunity to pursue his passion for painting.

For many years, after his unsuccessful foray in London, Churchyard eschewed public exhibition. During the more than thirty years that he built up a portfolio of work, that would eventually secure him an honourable place in English landscape painting, virtually his only critics were his friends, his family and himself.

On most days Churchyard painted outdoors making small oil and watercolour sketches of the familiar scenes around Melton and Woodbridge. He rarely painted outside the locality and often took his artistic children with him on painting excursions. His nine children, particularly his seven daughters had varying, but limited, artistic abilities and were imitators of their father's style. Like him, they were all prolific artists, rarely destroying any of their work. Laura's watercolours are usually acknowledged to be closest to those of her father. Charley was the only one who regularly signed, dated and named the venues of his paintings. All this made it difficult to accurately attribute some of the paintings produced by the Churchyard family.

Churchyard became a master of capturing the exact time of day or the effects of changing weather in a fleeting moment. To him these sketches were finished works in themselves. His friend Bernard Barton wrote ‘He will dash you off slight and careless sketches by the dozen, or score, but for touching and re-touching, or finishing, that is quite another affair, and has to wait, if even to be done at all’.

When, in 1850, he resumed exhibiting, it was with the Norwich School of landscape painters, including John Middleton, James Stark and Robert Lemain, at the Suffolk Fine Arts Associations inaugural exhibition. In 1852 he exhibited again with the same group of artists.

E

xamples of his work are on display in Woodbridge Museum and photographs of two of then are shown below.

The Seckford Almshouses

The Avenue

Churchyard was a collector of English Landscape painting from early on in his career. In 1831, before setting off on his attempt to establish himself as a professional artist in London, he put up for sale by auction a ‘valuable collection of paintings consisting chiefly of works of some of the most esteemed Masters of the British School - Gainsborough, Morland, old John Crome, and others’. Later the habit of buying, selling or exchanging paintings, particularly those of the Norwich School, became an essential feature of Churchyard’s everyday life. There is no evidence that he made money from picture dealing. It is more likely that his addiction to acquiring new paintings was a drain on both his money and his time, and was thus a major contributor to his eventual financial failures.

Churchyard advised Barton on what paintings to buy and these paintings were eventually seen by FitzGerald. When he learnt that Churchyard had advised Barton on the choice of paintings he asked if Churchyard would do the same for him. FitzGerald was then aged 27 and Churchyard 39.

Churchyard, Barton and FitzGerald along with George Crabbe, vicar of Bredfield, eventually started to meet regularly and referred to themselves as the ‘Woodbridge Wits’. They read favourite books together, discussed new ones and criticised each others latest pictures. The conversations being ‘oiled by quality wines-and porter’.

Of the surviving seventy or so letters from FitzGerald between 1839 and 1846 more than three quarters deal with the sport of ‘picture-hunting’. They are littered with comments such as ‘going today to look at some pictures for auction at Phillips' - oh Lord, Lord’. There can be no doubt that Churchyard's infectious enthusiasm in searching for unrecognised masterpieces quickly spread to his new friends. The question that cannot be answered is whether the acquaintance with FitzGerald, who never had to earn a living, may have resulted in Churchyard buying more paintings that he would have otherwise have done so and thereby hastened his eventual bankruptcy.

By 1851 Churchyard had was in financial problems and, in 1854, he was designated ‘an insolvent’. The family had to leave the splendid setting of Marston House and live for a time at Melton.

By 1856 Churchyard’s financial situation appears to have improved. There are records of him buying pictures again and the family returned to Woodbridge, renting the substantial Hamblin House a hundred yards further down Cumberland Street on the opposite side to Marston House.

In 1558, Isaac Churchyard, the last of Churchyard’s uncles and aunts, died and he was the sole heir to what remained of his grandfather’s estate. Two of the farms he inherited were taken over by his eldest son Tom. He had always wanted to be a farmer and had started out with forty acres at Ufford. In 1852 he decided to go to America but returned following the death of Isaac.

If Churchyard was hoping for a significant inheritance from the death of his uncle he was soon disappointed – the estate was just sufficient to cover his uncle’s debts. Tom became a tenant, rather than owner, of the two farms.

In 1863 Tom decided to start a new life in the colonies. With his wife and their three children he embarked for Quebec. The ship floundered off the Canadian coast and Tom was the only member of his family to survive. Little is known of his later life. He eventually ended up in New Zealand were he died in 1896.

Churchyard’s debts continued to increase, and when he died on the 19th August he was bankrupt. His obituary in the Ipswich Journal summed up his life thus:- "His devotion to the fine arts was to him the very breath of life; and it may be questioned whether there is now living a finer judge of the Early English Landscape School than he was. Old Crome, Wilson, Gainsborough, Morland - in these more particularly; but above all and before all, in Old Crome he revelled and delighted. Indeed, he might almost be said to be the man who first brought Crome's pictures into the high estimation they are now held; at all events, he was the first who ever ventured on a ‘long price’ for his works. Those who knew him best can yet picture the delight with which he introduced them to some new acquisition, or mayhap an old acquaintance, parted with or exchanged years ago, welcomed back to his collection like a lost sheep returned to the fold. He himself was an artist of the highest excellence, and his works almost invariably show his affectionate reverence for the great masters we have named. Crome he studied and copied with such faithful exactitude as (on more than one occasion) to deceive the most eminent connoisseurs. An ardent lover of nature, he might daily be seen sketching some favourite spot; and his pictures are conspicuous for their fidelity and truthfulness."

A Public Appeal for Churchyard’s destitute family was launched and raised £600. Apart from his close friends, the auctioneer Ben Moulton, FitzGerald and FitzGerald’s brother, all other contributors to the appeal were members of the legal profession. Woodbridge tradesmen were notably absent; they presumably still bore the scars of Churchyard’s unpaid bills.

In March 1866 there was a sale of many of Churchyard’s collected works of art. His twenty-three Crome oils fetched £650, four Constables £120, three Gainsboroughs £115 and five Morlands £140. All the paintings he had produced himself were left to his daughters.

Churchyard’s widow and their seven daughters moved across Cumberland Street and rented Penrith House a much plainer building than their previous home. It was all too much for Mrs Churchyard who died just over a year later. The eldest daughter Ellen, who was always the most practical and worldly of the children, set about completing the winding up of her father’s estate and then went into service in Norwich.

The fifth daughter, Elizabeth, eventually followed her example but the others carried on regardless with out any great concern for the future. Edward FitzGerald had once obliquely referred to Churchyard as ‘a gentleman in straitened circumstances who had a family of daughters who were allowed to stay at home and amuse themselves in faddling occupations, instead of being forced to go out into the world. He hasn't a penny yet there are his daughters all at home, kept like white mice.’ The uncomplimentary remark got around and was remembered. In later years, when some of the sisters continued to behave in a manner that set then apart from others, some townspeople would refer to them as ‘the little white mice’. They had all been educated above their class. Without the prospect of a dowry, they had no prospect of finding a husband.

FitzGerald was even harsher regarding Charley - the youngest son - who was in a lawyer's office at Ipswich and, although twenty-nine, had not qualified. Of him FitzGerald wrote ‘The worst is the younger son, Charley, who having been brought up to be idle, is now not only idle but dissipated; and will wring all their money out of them.’

Churchyards eldest daughter Ellen was the only one of his children that FitzGerald had any regard for. When she eventually returned to Woodbridge after working in Norwich it was as housekeeper to her father’s friend Ben Moulton. When he died in 1883 he left Ellen an annuity of thirty pounds for life. This enabled her to live in some comfort in a house in New Street. Soon after she took in Charley who by then was doing the accounts for a Woodbridge butcher. Ellen was given a place in the Seckford Almshouses in 1903 and three years later she died.

Emma, Laura, Anna, Harriet and Kate, the Churchyard sisters who had remained in Woodbridge, eventually realized they had to earn some money and they started by teaching girls of their own class, or from a little below, whose parents wished to see them advanced in a ladylike manner. Three of the sisters also managed to sell some paintings via the annual exhibition of the Ipswich Fine Art Club. In addition to their paintings the sisters also offered handicrafts for sale - beaded bags, cloth slippers, photo-stands, birthday cards, blotting books and painted stools. Several of the sisters offered linen doilies and pen and ink drawings.

Penrith House, Cumberland Street, the home of four of Churchyard’s daughters from 1879 until they moved into the rooms above the Seckford Library in 1891.

A doily attributed to Harriet

In 1879 the post of librarian at the Seckford Library became vacant and it was offered to Laura. With it came accommodation and she was able to live there with Anna, Harriet and Kate. (Emma the other sister who had been living with them died a year earlier). Visitors to the library would find the four of them sitting round a table either playing patience or seriously intent upon their work of stitching or drawing.

Kate died in 1888 and her place in the accommodation at the library was taken by Elizabeth who, by then, had given up her job as a servant. When Laura died in 1891 the Seckford Trustees passed the Librarianship to Harriet.

Anna died in 1897 and Elizabeth in 1913. This left Harriet on her own. She was the least reclusive of the sisters who had lived at the library. During the 25 years she served as librarian, she had an easy rapport with young and old. Vincent Redstone recalls ‘The appearance of Miss Harriet Churchyard as she sat at her library table was stately yet homely, striking and pleasing ... she would unbend to converse jocularly and wittily with those whom she knew as her frequent visitors and esteemed to be her friends. To the young folk she was especially attractive.’

When Harriet reached the age of ninety the Seckford Trustees granted her a pension and allowed her to remain living above the library until she died in 1927.

Churchyard’s Artistic Legacy

When Thomas Churchyard realized his health was failing he set about dividing all the paintings he had produced among his seven daughters. It is then that he made his much quoted prophecy: ‘My dears, there will not be any money for you when I die, but I will leave you my paintings which one day will be worth more than any money I could ever hoped to have made’. Churchyard wrote the name of one of his daughter, along with the initial TC, on each his oil paintings. He also produced an album of his water colours for each daughter.

His daughters were united in their belief that their father’s abilities would eventually receive the recognition it deserved. They kept their collection of his works largely intact and to it they added their own paintings. When each one died they passed their collection to the remaining sisters.

When Harriet, the last of his daughters died, her brother Charley is reputed to have rushed over from the Seckford Hospital to ask ‘where is the money’. Everything that had survived from Thomas Churchyard’s household was now his – including all the paintings that Thomas had left in care of his daughters. By April 1927 the paintings had been auctioned. Charley made £600 from the sale. By the time he died twenty months later he had worked his way through all but £225.

The sale at Woodbridge was not organised in a manner likely to bring the public recognition for which Churchyard's daughters had so long awaited. They were presented as a bewildering collection of four or five thousand paintings and drawings, together with a profusion of smaller sketches. The auctioneers offered nine hundred and eighty oils, a quarter of them already framed, in lots of twos, fours or sixes. Four hundred watercolours unframed but mostly mounted were sold in lots of from six to a dozen. Vastly more came pasted into albums or loose, as the contents of portfolios and boxes.

The catalogue warned that not all were by the artist himself. ‘Nearly all the under mentioned pictures are by members of the family of Churchyard, and many are by the late Thomas Churchyard. The initials TC where stated indicates that the picture is believed to be by him, but no guarantee is given.’ The auctioneers were safe in marking some three hundred and fifty of the oils in this way, for they were those that had been initialled by Thomas when giving them to his daughters and attaching one or another's name. No such distinction was attempted in the catalogue in the case of the watercolours and drawings.

Nevertheless, the wider appreciation of Churchyard's abilities started with that sale. The variety and freshness of his works puts them among the most attractive, as well as the most notable of English landscape paintings of the time. In his lifetime of sketching and painting, Churchyard set down as full and heartfelt a record of his birthplace and its surrounding countryside as any English artist has ever achieved.

The largest public collection of his works are in Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, and there is a smaller collection in Woodbridge Museum. The Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, and the Castle Museum in Norwich, each have a work.

The View on the Deben (formerly The Barge at Melton Dock) now hangs in Tate Britain in London alongside the works of Churchyard's lifelong heroes Gainsborough, Cotman, Constable, and Crome.

Thomas Churchyard of Woodbridge, D Thomas, 1966.

Painting the day: Thomas Churchyard of Woodbridge, W Morfey, 1986.

The Search for Thomas Churchyard, R Blake, 1997

Last edited 16 Aug 23