Edward FitzGerald - Translator of the Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám

Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883) spent most of his life in, or near, Woodbridge. His mother was one of the richest commoners in the land and consequently he never had to work for a living. He spent most of his time cultivating friendships and winning the affection and respect of the likes of Tennyson, Carlyle and Thackeray. His first translation was not published until he was 44.

Throughout his life he was shy and lacking in self confidence and needed the company of friends to bring out his drollery and good fun. He believed that he lacked originality but thought that he was a good judge of the work of others.

Edward’s parents were from good Irish families, but they were not of equal standing. His mother, Mary FitzGerald, was from a family having several large country estates in Ireland and England. Edward’s father, John Purcell, was the son of a wealthy Dublin physician and his mother was a FitzGerald - the families had a habit of marrying cousins. Edward was well aware that intermarriage amongst relatives brought problems and he blamed the eccentricities of his family upon their inbreeding. He used to enjoy saying that all of his family were mad so at least he had the advantage of knowing he was insane.

Edward’s parents were given Boulge Hall, Bredfield, as a wedding gift by the bride’s father but it was still held by a sitting tenant, the wife of the former owner. At the time of the sale she had reserved the right to live there until her death. Her longevity was to prevent the couple from taking possession of the house for 35 years. After his parents married in 1801 they rented Bredfield White House which stood about a mile away across fields from Boulge Hall.

Edward was born on 31st March 1809 at Bredfield White House and he was christened at Bredfield Church. He was the last of his parents’ seven children.

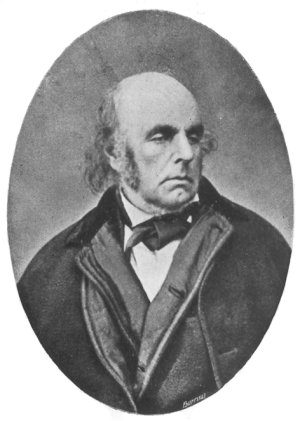

Edward's father, John Purcell, trained as a lawyer but never practised. He was an MP and in his later years he made an unfortunate investment which resulted in his bankruptcy. He was a caring and loving father but is often described as ineffectual. This was probably his only shield against his overpowering wife Mary FitzGerald. In 1810 she was left the major part of the wealth of a great aunt and it made her one of the richest commoners in the land.

Mary moved to London soon after receiving the inheritance and subsequently only visited her husband and children occasionally. Distancing oneself from one’s children seemed to run in her family. Her mother had demanded that her children address her as Mrs FitzGerald.

In 1818 Mary’s father died and she became even richer - she had become sole heiress to the FitzGerald fortune on the death of her brother in 1807. Because the inheritance was so large, John Purcell agreed to change the family name to FitzGerald although there was no legal requirement to do so. Thus, at the age of 9, Edward Purcell became Edward FitzGerald. Shortly after Edward, and his two brothers, were sent as boarders to Bury St. Edmund's Grammar School.

In 1825 the family left Bredfield White House after renting it for nearly a quarter of a century. They moved to Wherstead Park, near Ipswich, overlooking the broad estuary of the River Orwell. Edward's father took up sailing and FitzGerald was drawn in as well. Of all the family houses in which FitzGerald lived it was the only one he wrote about with affection. There were excellent book shops in Ipswich, good access to London and a wide variety of local acquaintances, including minor writers and painters.

Edward's parents John Purcell and Mary FitzGerald.

Boulge Hall, Bredfield, given as a wedding gift

by Mary FitzGerald's father.

Bredfield White House where Edward FitzGerald was born in 1908.

Most of the house was demolished in the 1950s.

The Cambridge Friendships

FitzGerald entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1826. His first year there appears to have been solitary but then he was joined by one of his school friends, James Spedding, who became a member of the Apostles, Cambridge’s most elite club. In Spedding’s company FitzGerald was relaxed and his qualities were revealed to Spedding’s other friends, many of whom were in the Apostles. Soon his life at University centred on a group of companions with whom he would remain close friends all his life. They included William Thackeray, John Allen and William Bodham Donne.

FitzGerald received a handsome allowance from his father while at University. This continued after he graduated, but it was on condition that he escort his mother in London whenever she so desired – an obligation which he accepted with reluctance. The allowance, and finally a sizable inheritance when his mother died, meant that he never had to earn money throughout his life and was thus never under pressure to establish a career.

After graduating from Cambridge in 1830 FitzGerald took lodgings in London so that he could be an escort for his mother. However, he retained his digs at Cambridge to enable him to continue to meet his old friends there. It was during one such return visit that he met the poet Alfred Tennyson and they became lifelong friends.

FitzGerald also often went to stay with his favourite relative, his eldest sister Eleanor. She had married a Norfolk squire and moved to Geldeston Hall near Beccles. FitzGerald loved her deeply and soon acquired a great affection for his brother-in-law. He found their home the perfect restorative and he subsequently visited them often. His letters are full of the idyllic life there and it was where he wished to be buried.

Geldeston Hall, near Beccles.

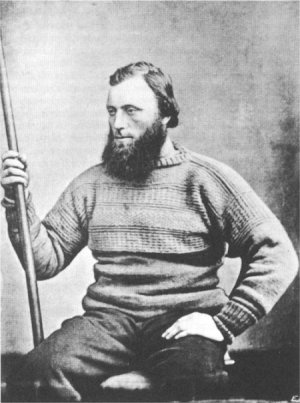

In 1832 FitzGerald sailed from Bristol to Tenby to visit his friend John Allen. On the steam packet from Bristol he had an enjoyable conversation with a sixteen year old boy, William Browne. He lacked any of the intellectual interests of FitzGerald but made up for this by good manners and spontaneity. After his planned visit, FitzGerald stayed in the same boarding house as Browne and they became close friends. Until Browne’s marriage in 1844 the two met frequently and had at least two holidays together each year. Thereafter they remained in contact but met less often. FitzGerald’s letters to his other friends often contained references to Browne, extolling his unspoiled simplicity, his intelligence which had been untainted by a university education, and his singular abilities at hunting, shooting and fishing; activities in which FitzGerald had never before expressed an interest.

There is much debate about the nature of FitzGerald’s relationships with his many close friends who were, with only a few exceptions, men. The most balanced analysis of this subject appears in Robert Martin’s book ‘With Friends Possessed’. He writes that ‘it is impossible to be precise about FitzGerald’s feelings for Browne, but any name but love would surely falsify them’. He goes on to discuss the spontaneity and freedom with which FitzGerald so often spoke of his attraction to Thackeray and Allen, then to Brown, and later to Posh Fletcher and comments that ‘only the most innocent and unself-conscious love could permit itself to be spoken of in such rhapsodic terms without embarrassment’.

FitzGerald was not as emotionally involved with his other close friends who included Donne, Alfred and Frederick Tennyson, Carlyle, Barton, Crabbe and six others.

William Browne

Meeting these friends, or at least writing to them, seemed essential to FitzGerald’s well being. He explained this thus:- ‘One’s thoughts and feeling, for want of communication, become heaped up and clotted together, as it were: but with a friend one tosseth them about, so that the air gets between them, and keeps them sweet.’ FitzGerald wrote with enormous charm and usually with consummate ease and the four volume collection of his correspondence is considered by some to be a literary achievement to rival the Rubáiyat.

As well as visiting his friends, sister and mother, FitzGerald also spent time at the family home at Wherstead Park. It became a focus for poetry circles and through these FitzGerald was introduced to Elizabeth Charlesworth and Lucy Barton. He fancied himself in love with the former and, much later, had a miserable marriage to the latter. He mentioned Elizabeth in his letters to Thackeray, Donne and Allen. Then, as he saw his friends drifting in to matrimony, he wrote asking whether he too ‘as a true bachelor’ should consider marrying her. They all seemed to interpret these letters as an invitation to discourage him from marriage and that is what they did. There is no evidence to suggest that Elizabeth was ever aware of the idea.

Wherstead Park, FitzGerald's home from 1825 to 37.

The faded tapestry of country town life

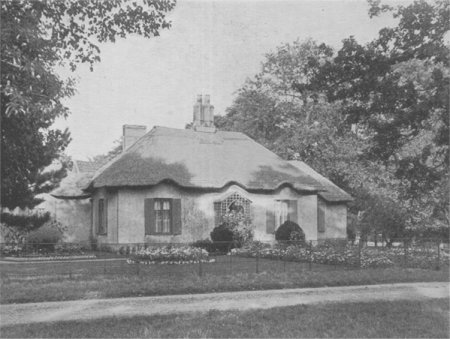

In 1835 FitzGerald's family were at last able to move into Boulge Hall and he joined them in order to be near his younger sisters Lusia and Isabella whom he felt had been abandoned by their mother. Two years later he found a way of being able to provide support for them without having to share a house with the rest of his family when they came to Boulge. His solution was to move into a cottage near the gates into the grounds.

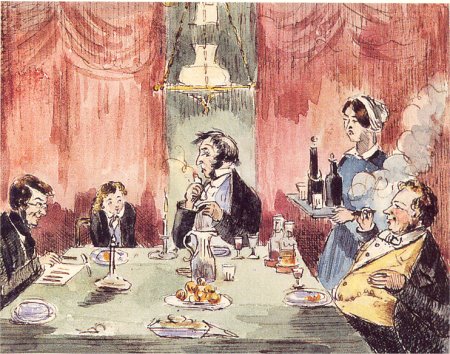

At Boulge he built up a new circle of friends. He first met the Rev. George Crabbe and Vicar of Bredfield. FitzGerald often used to visit the Crabbe family after dinner and sing glees with them before retiring to the vicar’s study. The friendship lasted until Crabbe died. His eldest son then succeeded his father in FitzGerald’s affections. He later wrote that his first impression of FitzGerald was that he was 'proud and very punctilious ... always like a grave middle-aged man: who never seemed very happy or light-hearted, though his conversation was most amusing sometimes'.

Shortly after meeting Crabbe, FitzGerald became friends with Bernard Barton. He was a Quaker and minor poet who earned his living as a bank clerk. Barton never thought that his verse rose to great heights. His desire was ‘to be a household poet with a large class of readers’. His twelve volumes of verse now gather dust in archives but, in his day, he was widely known as ‘the author of much pleasing, amiable and pious poetry, animated by feeling and fancy, delighting in homely subjects, so generally pleasing to English people.’

The cottage near the gates of Boulge Hall. It was

FitzGerald's home from 1837 to 1853.

Barton was also a friend of Thomas Churchyard, a liberal and learned advocate at the Suffolk assizes and a talented amateur artist who took every opportunity to paint and sketch Woodbridge and the surrounding countryside. He eschewed public exhibitions after an unsuccessful attempt to become a professional artist in London. When he died his paintings were left to his daughters. When the last of them died in 1927 they were sold off and the wider appreciation of Churchyard's abilities started. He is now is recognised as an accomplished landscape painter.

Churchyard had advised Barton on what paintings to buy and these paintings were eventually seen by FitzGerald. When he learnt that Churchyard had advised Barton on the choice of paintings FitzGerald asked if Churchyard would do the same for him.

FitzGerald, Crabbe, Barton and Churchyard started to meet regularly at Boulge cottage and referred to themselves as the Woodbridge Wits. They read favourite books together, discussed new ones, and criticised each other’s latest pictures. When they first started to meet, FitzGerald was aged 28, Crabbe 52, Barton 53 and Churchyard 39. The Woodbridge Wits was almost a rebirth of FitzGerald’s close group at Cambridge but he was in no danger of confusing the two. He called it ‘the faded tapestry of country town life’ and he kept up a stream of correspondence with all his former friends and made frequent visits to meet them.

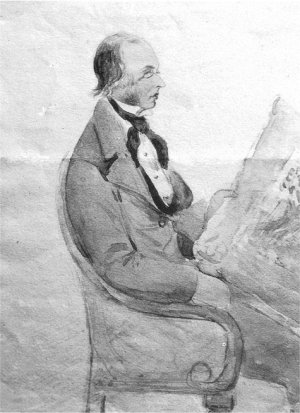

A satirical sketch by Ellen Churchyard of a meeting of three of the Woodbridge Wits - Thomas Churchyard (left), Edward FitzGerald (centre) and Bernard Barton (left). The young boy is Thomas Churchyard's son Tom.

For a time FitzGerald spent freely on pictures in London but by 1842 his enthusiasm for ‘picture hunting’ was on the wane. On his visits to London he often met up with his literary friends and was led to consider his own literary and poetic talents but he had little drive to emulate them. He described his state thus ‘I know that I could write volume after volume as well as other of the mob of gentlemen who write with ease, but I think unless a man can do better, he had best not do at all’. He probably remained diffident about his literary and poetic talents because he was constantly in the company of men whom he knew in his heart to be infinitely his superiors as writers - Thackeray, Tennyson, Carlyle and on one occasion Dickens. What he did not consider until later was the possibility of translation, the verbal equivalent of the rearrangement of other men’s art, something that he had often attempted with painting and music.

A drawing by Harriet Churchyard showing

Edward FitzGerald inspecting a painting

The Influence of Cowell

FitzGerald’s translations arose as a result of a meeting in 1844 with the 18 year old Edward Byles Cowell. He had been a brilliant pupil at Ipswich Grammar School and was a self taught linguist who had had translations of Persian verses published in the Asiatic Journal when he was only sixteen. In that year his father died and Cowell had to abandon any hopes of an academic career in order to takeover the family printing business which he ran effectively for some years. Nevertheless his passion for languages remained.

The friendship between FitzGerald and Cowell developed into a deep mutual intellectual admiration. What FitzGerald found so appealing in Cowell was that he learned languages as a way to unlock literature rather than as an end in themselves. A quarter of a century later FitzGerald said, ‘I have met and known many learned and clever men but Edward Cowell is the greatest Scholar’. Their friendship survived Cowell’s marriage a year later to Elizabeth Charlesworth, the woman to whom FitzGerald had once thought himself in love. Against FitzGerald's advice, Cowell eventually went to Oxford University in 1851 and he was subsequently appointed professor at Calcutta University and then at Cambridge University.

FitzGerald soon became the pupil of the younger man. In 1846, with Cowell’s encouragement, he started writing a modern ‘Platonic’ dialogue on how contemporary education warped young men’s minds by teaching them only bookish subjects. It was eventually published as Euphranor in 1851. By that time he was following Cowell’s advice to learn Spanish and thereby read the works of Calderón. By 1853 FitzGerald was proficient enough to publish a translation of six dramas by Calderón. He allowed his name to appear on the title page in order to distinguish his translation from another appearing at the same time. All his other translations were to be published anonymously. His work came in for criticism for its very free translation, something FitzGerald openly admitted. His policy in this, and later translations, was not to aim for a literal rendering but to create an English equivalent in the spirit of the original.

Cowell encouraged FitzGerald to lean Persian in 1852 and four years later he was proficient enough to publish a translation of Jámi's allegorical Persian poem Sálámán and Absál.

The translation of Sálámán and Absál was undertaken during a time of turmoil in FitzGerald’s life. In 1848 Bernard Barton died. His daughter Lucy was facing destitution so FitzGerald immediately set about editing some of Barton's poems so they could be published in an anthology. Within a year, for some reason which is still unknown, he had promised to marry Lucy, who was a year his senior. However, the marriage had to be delayed because FitzGerald’s father was facing financial ruin.

By 1853 FitzGerald’s father had died and his mother turned Boulge Hall over to FitzGerald’s elder brother John. This prompted FitzGerald to leave Boulge cottage and to move into lodgings at Farlingaye Hall, Woodbridge. His landlords, the Smiths, had previously occupied a farm near Boulge Hall.

FitzGerald’s mother died in 1855 and she left him £50,000 which made him financially secure for the rest of his life. A year latter he married Lucy Barton and they set up home in London but within nine months they had separated. He settled £300 per annum on her provided she did not live in Woodbridge - an action that was considered disgraceful by many residents of the town. Apart from a few months at Farlingaye Hall, FitzGerald also managed to stay away from Woodbridge during the next three years by spending long periods at his lodgings in London or with either his sister Eleanor or the Browns.

Lucy Barton who married Edward FitzGerald in 1856.

In 1855 Cowell gave FitzGerald a copy he had made of a manuscript of the Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám. Within a year FitzGerald was at work on the translation that made him famous. He published it anonymously, at his own expense, in 1859. It failed to attract attention until a copy was purchased from a ‘quick sale’ box in 1861 and given to Dante Gabriel Rossetti who hailed it a masterpiece.

A second edition, published in 1868, was reviewed in glowing terms especially in the United States. Soon there was, as FitzGerald put it, ‘a little craze’ over the Rubáiyat in America. By 1875 rumours about the Rubáiyat’s authorship were circulating there and FitzGerald was upset when his publisher obliquely revealed his identity in an advertisement a year later.

FitzGerald produced four editions of the Rubáiyat altogether, continuing to add and subtract stanzas and to refine the language. The first edition contains all the oft quoted verses such as:-

A book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread – and Thou

Besides me singing in the Wilderness –

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

and:-

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on; nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

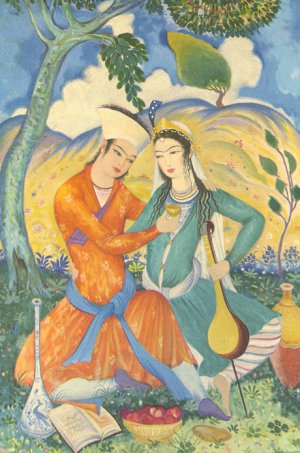

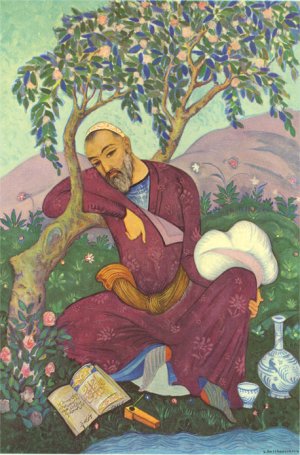

Some editions of the Rubáiyat are beautify illustrated and pictures on the right relate to the verses quoted above.

Before FitzGerald’s translation of his work, Omar Khayyám was little known even within the Middle East. He lived in 11th century Persia and was primarily an astronomer, mathematician and philosopher. He reflected on life and the human condition and his thoughts on both are encapsulated in his Rubáiyat. This was a collection of quatrains - four line stanzas – each of which was independent of the others. They were not written down during Khayyám’s lifetime and the manuscripts that were produced later contain many quatrains written by others in his style.

FitzGerald used about half of the stanzas he was given by Cowell and he created some new stanzas by taking two lines from one and combining them with two lines from another. He also imposed order on the ones he used, creating a narrative pattern that moves from morning to night, and setting it in a Persian garden. The result should thus be viewed as an original English poem that reflects the spirit of the Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám.

Omar Khayyám made heavy use of metaphor and because of this readers are often able to see a reflection of their own ideas in his poetry. Thus every generation is likely to have its own interpretation of Khayyám’s philosophy.

What we see in FitzGerald’s lyrical interpretation of the Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám is probably FitzGerald’s view on life and the human condition. And, as with Khayyám’s original, every generation of readers of FitzGerald’s Rubáiyat will have its own interpretation of FitzGerald’s philosophy. So in that respect both works are timeless.

FitzGerald at one time declared himself to be ‘akin’ to Omar and in a letter to Tennyson he characterised the Rubáiyat as being Epicurean. This has led some to suggest FitzGerald was attracted to the Rubáiyat because it expressed the Epicurean tenet that you should not imagine that God is concerned about human beings and their behaviour, and that you should thus not let the fear of the wrath of a God inhibit your actions.

FitzGerald often expressed doubts about religion and in his later years rarely attended church. It is also worth noting that FitzGerald and the devout Cowell never agreed on the ethics behind Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyat and that many scholars are still locked in debate on this subject. FitzGerald was certainly Epicurean in other respects. He despised ostentation and extravagance and this was apparent in his clothing, accommodation, possessions and even food - he ate mainly bread and fruit. Much of his life was devoted to keeping his friendships fresh by writing a constant flow of cultivated letters. He avoided discussing politics and seemed to think that marriage and sex were of dubious virtue.

A book of Verses underneath the Bough

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

In 1859, soon after the publication of the Rubáiyat, FitzGerald was driven to deep despair by the death of William Browne. Later that year FitzGerald spent six months in lodgings at Lowestoft and searched for companionship among the fishermen there. By 1860 he was back in Woodbridge. His old landlady at Farlingaye Hall was ill so he moved into two rooms above a gun shop on Market Hill. His friend George Crabbe had died and Thomas Churchyard was in serious financial difficulties and was to die bankrupt 5 years later.

The period in Lowestoft rekindled FitzGerald’s attraction to the sea and sailing. His father had been a Member of the Royal Yacht Club and had taken part in notable regattas and other allied events. Edward had sailed with both his father and grandfather and so it is not surprising that eventually he had a small boat on the Deben estuary. The competitive and social sides of yachting were an anathema to him, what he wanted was an intimate relationship with the sea and the coast.

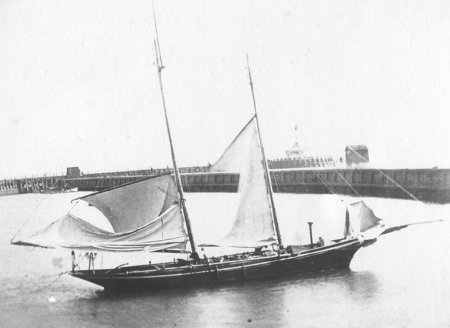

In 1861 FitzGerald replaced his small boat with a two-ton, sixteen–foot river boat named Waveney. Two years later he had a forty-three-foot schooner built in Wivenhoe, Essex. He named the boat Scandal because scandal went faster than anything else in Woodbridge. Her skiff was appropriately named the Whisper. Edward was quite happy to let his crew sail the boat. He said that ‘as in other affairs of life, I only sit by and look on’.

From 1864 his constant companion on the boat, either as a guest or a member of the crew, was a young Lowestoft fisherman ‘Posh’ Fletcher. Their friendship eventually ended in 1873 after a long running dispute about a fishing enterprise they had set up in 1868.

FitzGerald’s friendship with the young, uneducated, fisherman aroused some comment amongst the townspeople many of whom were still angry about his treatment of Lucy Barton. They found it hard to come to terms with man who had a sharp wit and who dressed like a down-at-heel countryman rather than as a gentleman. Because of his unconventional appearance and behaviour Woodbridge children called him ‘Dotty’.

Although FitzGerald’s relationship with many of the townspeople remained strained. He nevertheless welcomed the company of a number of men. They included John Loder the printer, Herman Biddell a landowner at Playford and Frederick Spalding a bright young merchant’s clerk, with interests in arts and artefacts, whom FitzGerald help set up in business.

Herman Biddell, in a centennial tribute to FitzGerald, recalls his passion for talking about literature and his reluctance to discuss religion or politics. He went on to write he ‘knew of no keener eyes that FitzGerald’s for the beauties which Nature puts before us all. The water-lily on the pool, the indigo of the deep North Sea, the ever-varying leaf tints, the birds, the clouds, the sky never failed to give him infinite pleasure.’

FitzGerald’s love of the river and the sea remained undaunted even after he had sold his schooner. He would often been seen at his favourite seat at Kyson quay or out on the river with his boatman Ted West.

FitzGerald's schooner which he named Scandal

The Lowestoft fisherman ‘Posh’ Fletcher.

In 1864, after many years of living in lodgings FitzGerald finally bought a place of his own. The estate of Melton Grange was parcelled off when it changed hands, and he bought Grange Farm, its former farmhouse, with six acres, for £730. He referred to it as a ‘rotten affair’ and was not sure what to do with his purchase, but he said he had talked so long of buying that he had to get something, even if he resold it at once.

Within a few months the builders were working on the first of his additions to the old farmhouse, but it was another ten years before he moved in and at last called it home. During this period he remained in his lodgings on the Market Hill and he published translations of more of Calderon’s plays and the Agamemnon - his finest translation after the Rubáiyat. By then his eyes were failing and he found it hard to read. His eyes had never been strong and, from about 1854 when he moved to Farlingaye, he had begun to ask local boys to read to him.

The farmhouse he had purchased was eventually converted into an impressive building. FitzGerald first added one large and airy room on each floor and a lavatory. Outside the ground-floor windows he built the handsome garden terrace that still stands. He planted the garden with the trees and bright flowers he loved, had a duck pond put in. He also bought more land to preserve his view of the river and furnished the house completely. Yet he could not summon up courage to move into it. He said ‘I believe I never shall do unless in a lodging, as I have lived these forty years. It is too late, I doubt, to reform in a house of one’s own.’ It was more than five years after he bought the house that he spent a night in it. He protested that he had no time for the responsibility of running a house, but he actually had that without living there, for he installed a resident couple to care for his nieces and other guests.

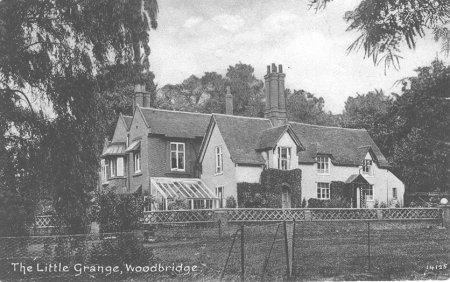

Grange Farm was part of the estate of Melton Grange.

When FitzGerald moved into it he renamed it The Little Grange.

When all other excuses failed him for not making Grange Farm his home, he put on another extension of two more rooms in 1871 but did not move in until 1874. The handsome and commodious house set in a large garden was far from the bustle of Woodbridge, with only the muffled sounds of Pytches Road to make him feel part of the life of the other townspeople. After a few months there he changed its name to The Little Grange.

FitzGerald allowed himself to be photographed for the only time in 1873. Four years later he and one of his sisters were all that remained out of the family of seven children. Many of his other close friends had also died and he met Alfred Tennyson for the last time when he made his only visit to Woodbridge in 1876. Tennyson stayed at the Bull Hotel, as did his brother Frederick when they came to see FitzGerald in 1872. Carlyle was the only other member of FitzGerald’s Cambridge circle to visit him. He spent a few days at Farlingaye Hall in 1859.

FitzGerald in 1873

Despite his poor eyesight FitzGerald was still working on translations and other literary projects. He was also keeping up his correspondence with his dwindling number of old friends and some new ones. In June 1883 FitzGerald wrote the last of his thousands of letters. In it he record "So I go on living a life far too comfortable as compared with that of better and wiser men". He died on the 14th June 1883 at Merton Rectory, Norfolk – the home of George Crabbe Jnr.

FitzGerald’s grave is at Boulge churchyard, near the family mausoleum. It was his wish not to be buried in the mausoleum. He wanted to be where he could hear the birds sing. Persian roses grow on his grave, one planted by the Omar Khayyám Club in 1896, and others presented by the Iranian Embassy in the 1970's. His young Woodbridge friend Frederick Spalding wrote ‘I shall never know or meet his like on earth (again) and I heartily thank God that I have known him well and in a small measure been able to appreciate him’.

FitzGerald’s grave at Boulge churchyard.

Source

Last edited 20 Aug 23