Thomas & John Clarkson - The Friends of Slaves

Introduction

The bicentenary of the passing of the 1807 Act to abolish the slave trade was marked in many ways but Thomas and John Clarkson did not always received adequate credit for their endeavours. In the case of Thomas the blame for this lies with a posthumous biography of William Wilberforce written by his two sons. They belittled Thomas’ achievements and made Wilberforce the chief architect of the abolition campaign. The brothers later apologised for what they had done but, by then, their original version had taken root in people’s minds.

John Clarkson (1764-1828) spent the last eight years of his life in Woodbridge and is buried at the parish church of St Mary’s. His brother Thomas (1760-1846) came to live in nearby Playford in 1816 and is buried there. Both their lives were defined by their fight against the slave trade and this pamphlet describes the manner in which they used their talents to help abolish it.

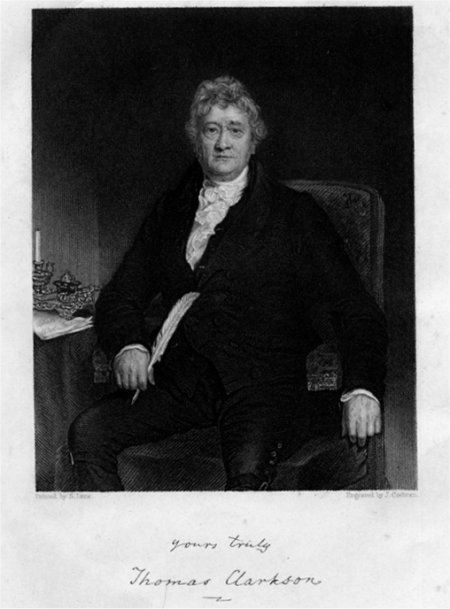

Thomas and John were opposites, both physically and in their characters. Thomas was tall and large whereas John was of slight build. Their personalities differed as much. John had a sunny disposition, was charming and easily likable. Thomas was haunted by the sufferings of others and developed ulcers. When John died, his sister-in-law, Catherine, wrote that ‘a fountain of innocent mirth is now closed up’. Thomas, in death, was remembered as an apostle and a martyr. Thomas was more apt to disturb people than make them laugh. From university days until death, Thomas' all consuming passion was the fight against the slave trade and the institution of human slavery. Coleridge called him a ‘moral steam engine’ and a ‘giant with one idea’.

Thomas Clarkson whose all consuming passion was the fight

against the slave trade and the institution of human slavery.

Their father was headmaster of Wisbech Grammar School and it was in the school house that Thomas was born in March 1760. Four years later John arrived.

As well as being headmaster, the Rev. Clarkson was also an afternoon lecturer at the parish church and curate in the neighbouring parish of Walsoken. One day after visiting the poor of that parish and returning in rain and wind after midnight, he died of a fever. Thomas was only six and John not yet two. Their mother, who was then 31, moved with her three children to 8, York Row, Wisbech., a house owned by her cousin. He, and her other numerous and well connected relatives, helped bring up the family.

Both boys attended Wisbech Grammar School. Thomas was destined for the church and John for the navy – the pattern for gentry families in those days. John left the Grammar School when he was thirteen and joined HMS Monarch as a cadet. It was a year after the outbreak of the American Revolution and John spent his active service on nine ships defending the West Indies.

His brother Thomas transferred to St Paul's School in London in 1775 and four years later attended his father's old college, St John's Cambridge. He graduated in mathematics in 1783 and later that year was ordained as a deacon. In 1784, he won a minor Latin essay prize and then decided to remain and enter the University’s most prestigious Latin essay competition. The topic, set by the vice-chancellor, was 'Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?' Clarkson admitted that his original motive in entering the competition had been to gain literary honour but, as he began to assemble material for the essay, he came to realise the true horrors of slavery. He won first prize and then, while riding to London, he had a revelation he descried thus ‘a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities come to an end.’ That moment changed the direction of his life and that of his brother John.

Before describing what happened next a short digression is needed to summarize how the Atlantic slave trade developed and the opposition to it.

8, York Road, Wisbech, the home of the Clarkson

brothers after the death of their father.

Painting of Wisbech Grammar School

Slavery was a major institution in antiquity. In both Greece and the Roman Empire there were slaves who had been taken in battle or from countries that had been conquered. Slavery continued after the fall of the Roman Empire but, by the eleventh century, there are indications that the nature of slavery was changing in Northern Europe. By 1200 it had vanished. Slavery continued, however, in the countries that bordered the Mediterranean. The sea and its shore were a permanent war zone between Christians and Muslims, and both sides made slaves of each other.

A new phase began in 1444 when a small fleet of Portuguese ships landed 235 black African slaves on the south-west point of the Algarve. The fleet was financed by Henry the Navigator who had claimed Madeira and the Azores for Portugal and then sent out probing voyages along the African Coast in search of trading opportunities. The first cargo of slaves was soon followed by more. Initially the slaves were unlucky individuals who had been kidnapped by the sailors but a year later they were obtained from local chiefs in return for European goods – woollen and linen cloth, silver, tapestries and grain.

African slaves began to perform many functions in Portugal and Spain. By 1452 they were also being used in sugar plantations on Madeira. Sugar cane was eventually introduced to the Caribbean islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico soon after the islands were discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Native Indians were paid to process the cane and to work in the gold mines. However, the indigenous population rapidly went into decline because of the diseases brought by the Europeans and because of deaths from hard work in the mines and in the fields. It was also soon apparent that the Indians were not such good workers as black Africans. So, in 1510, King Ferdinand authorized the dispatch of African slaves to the islands. This was the beginning of the slave trade to the Americas. By 1518 European diseases had brought about a complete collapse of the indigenous population of the Caribbean islands and the African slave trade across the Atlantic had become a major enterprise.

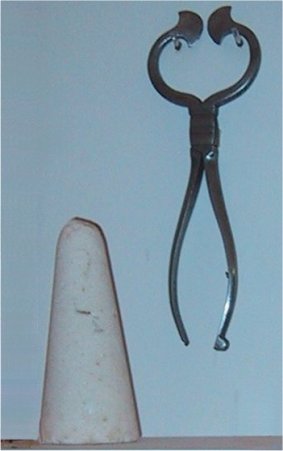

The Portuguese started to plant sugar cane along the coast of Brazil soon after they had discovered the country in 1500, but production was not significant until about 1550. Fifty years later Brazil was Europe’s most important sugar supplier and was by far the richest European colony. Growing sugar displaced all other forms of agriculture – something which had not yet happen in the Caribbean islands. Enslaved indigenous Brazilians were initially the main labour force but, by 1570, they had been replaced by African slaves. By the end of the sixteenth century all the features of slavery, that so appalled the abolitions two centuries later, were in place. The cones of sugar that rotted Elizabeth’s I teeth were the product of the Atlantic slave trade.

A cone of sugar and a cutter used to break it up. Such cones

first reached England from Brazil in the sixteenth century.

In 1444 the ships of Henry the Navigator (left) brought black African slaves to Portugal. In 1510 King Ferdinand (right) dispatched the first African slaves to the Americas.

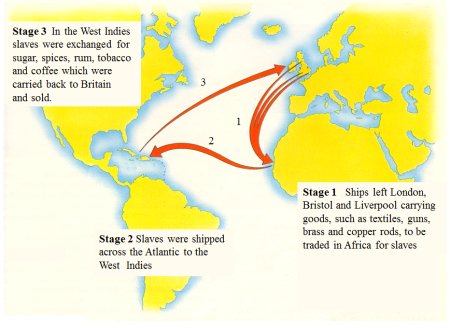

The Portuguese and Spanish dominated the early years of the trade and, by the mid seventeenth century, the Dutch and the French were the most active. By the mid eighteenth century Britain was dominant because of its naval power and because it had settled most of North America and had taken possession of many islands in the Caribbean. British slave ships also served the French, Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese colonies. These ships sailed a triangle shown on the map on the right. They carried trading goods from Liverpool, Bristol or London to Africa. They then carried slaves to the Caribbean or North America, and then sugar, coffee, cotton, rice, and rum back to Europe.

Of the 11 million African slaves that arrived in the Americas 3% was sent between 1444 and 1600, 16% between 1600 and 1700, 52.5% between 1700 and 1800 and 28.5% after 1800. Shocking as the figure of 11 million is, it does not included the estimated 4 million who died because of the appalling conditions on the slave ships and on the long treks from the interior of Africa.

The cruelty and ruthlessness that characterised the collection and transport of slaves continued once they had reached their destination. Work on the sugar farms was strenuous and there were many deaths owing to machinery. Life expectancy was short and most of the female slaves were unable to bear children because of malnourishment and hard work. Thus a continuous supply of new slaves was needed to replace those who had died. These features also characterised the slavery in the many mines opened in the sixteenth century from Mexico to Peru; and in Brazil after gold was discovered there at the end of the seventeenth century.

Only in the cotton and tobacco fields of North America were the conditions tolerable enough for slaves to have families and, as a result, the need for imported slaves diminished.

Thomas would eventually lay bare the full barbarity of the Atlantic slave trade and the common man in Britain soon wanted an end put to the evil business. The wealthy ruling class was, however, blinkered by the commercial benefits of the trade and proved harder to convince.

The Slave Triangle

From the outset of the Atlantic slave trade there were individuals who expressed doubts about the morality of it, and of slavery, but they were ignored. By the mid eighteenth century moral philosophers and intellectuals in Britain and France were condemning slavery but it was concerted action, rather than words, that would eventually cause change. That action was begun, in 1676, by American Quakers. Opposition to slavery gradually grew within their movement and, during the 1760’s, the Philadelphia Quakers and the British Quakers condemned all those who invested in the trade or supplied cargoes for it.

The American Quaker Anthony Benezet wrote a number of influential anti-slavery books which spread around the world and influenced people outside the Quaker movement. Benezet came to England to share his views with British Quakers and his companion William Dillwyn stayed to help them organise an anti-slavery campaign. Boneset's books were Thomas Clarkson’s key sources in preparation for his essay in 1784.

Another Anglican in England had already started his personal anti-slavery campaign some 20 years earlier. In 1765 Granville Sharp, a well connected pamphleteer, came to the aid of a slave who had accompanied his master to London as a servant and was then abandoned after being injured. When the slave recovered the former owner seized him again but Sharp managed to get the slave freed after a legal hearing. Word soon spread quickly in London’s black community that Sharp was prepared to go to court on behalf of slaves wanting freedom. In 1772 Sharp initiated what was to prove a landmark case. It was heard by the Lord Chief Justice and the ruling was interpreted as a declaration that that the condition of slavery did not exist under English Law.

In 1783 Granville Sharp’s attention was drawn to an account of one hundred and thirty two slaves being thrown alive into the sea from the English slave ship Zong. It later transpired that the act had been committed as part of an insurance fraud. Sharp failed to get anybody prosecuted for murder but a passionate salvo of letters he wrote spread the word of what had happened on board the ship. When the news reached the prominent Anglican clergyman, Dr Peter Peckard, it deeply disturbed him and he preached a sermon condemning the slave trade as a ‘most barbarous and cruel traffic’. Soon after, Peckard became vice-chancellor of Cambridge University he set the topic for the prestigious Latin essay competition which Thomas Clarkson won.

Granville Sharp went to court on

behalf of slaves who wanted freedom

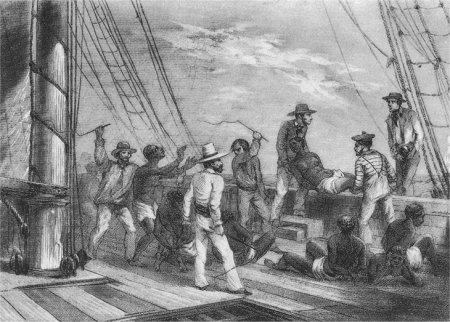

One hundred and thirty-two slaves were thrown

overboard from the slave ship 'Zong'.

This brings us back to Damascene moment when Thomas had the revelation that 'if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities come to an end.’ His immediate action was to solicit the help of his brother John to translate the essay into English and expand it to book length. At the time John was one of the 1200 lieutenants on half-pay following the end of the American War of Independence.

When the book was finished Thomas went in search of a publisher and he eventually chose a Quaker printer, James Phillips, who published the book in 1786. Philips also introduced Thomas to six Quakers who had formed a committee three years earlier to agitate against slavery and the slave trade.

A miniature of John Clarkson

in his naval uniform.

The committee of Quakers had worked valiantly, sending articles to a dozen newspapers and distributing a fifteen-page pamphlet to the royal family, other notables and members Parliament. Ten thousand more copies had been sent throughout the country. Yet no one paid much attention.

They knew that their strenuous pleas against slavery had been ignored simply because they were Quakers. The Quaker’s strong views, dress and mode of speech and writing had long since set them apart from most people. To influence public opinion they needed Thomas Clarkson - a talented young Anglican willing to devote all his energy to the movement. The time had come to form a new anti-slavery organization – one that could not be written off as being controlled by a fringe sect. After much careful planning a committee of a dozen men was agreed on, nine Quakers and three Anglicans – Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and Philip Sansom. Sharp, the elder statesman of anti-slavery efforts, was the chairman.

At their first meeting in 1787 the committee had to decide whether they were going to press for the abolition of the slave trade or for the emancipation of all slaves. They opted to focus on the abolition of the slave trade because, even if Parliament passed a law that all slaves should be free, there was no certainty that the West Indian colonial legislators would accept it. From that point on the group became known as the London Abolition Committee.

Thomas, the only member of the committee without professional commitments, took on the essential job of seeking out every possible source of information that could be laid before Parliament. Before he set about acquiring this data, the committee asked Thomas to met with William Wilberforce to ask him if he would be the voice of the anti-slave trade campaign in the House of Commons. Wilberforce had a reputation for integrity. He was a political independent and, most important of all, he was a close friend of William Pitt, the Prime Minister. Pitt had great respect for his friend's abilities as a speaker, he thought, Wilberforce had ‘the greatest natural eloquence in England’. When Thomas put the proposal to Wilberforce he replied that ‘provided no person more proper could be found’, he would raise the issue in Parliament.

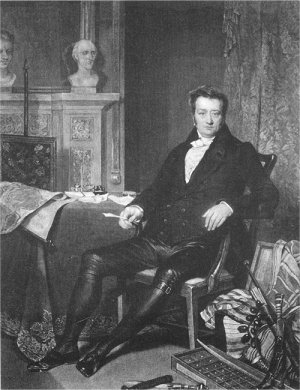

William Wilberforce who agree to be the voice of the

anti-slave trade campaign in the House of Commons.

Thomas set out to gather information about the slave trade, gaining first hand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at Bristol and Liverpool. His brother John acted as his secretary and then, as one of his agents, spent six months in Le Havre studying the French slave trade.

Thomas also collected examples of African natural products and workmanship that demonstrated the fertility of Africa and the skills of its inhabitants. He carried them around with him in a trunk and used them to argue that Africa offered Britain the prospect of a rich trade in something other than slaves.

On his way back from Liverpool Thomas visited Manchester, a city that sold goods to slave ships. There he met two activists who had just organised tens of thousands of people to sign a petition that made the government withdraw a new tax on cotton cloth. They told him that anti-slavery spirit was so strong in Manchester that people now wanted to petition Parliament on this subject as well. This was just what Thomas and the committee had in mind as the opening stage of a national campaign. A few weeks after he left Manchester an anti-slavery petition was sent from there to Parliament. It contained more than ten thousand names, one out of every five people in the city.

When the 1788 session of Parliament adjourned it had been sent 103 petitions, signed by nearly 100,000 people, calling for abolition or reform of the slave trade. Petitions were a time-honoured means of applying political pressure in a country where less than one adult man in ten could vote for a Member of Parliament.

Thomas Clarkson and his chest of African goods.

Anti-slavery letters and articles appeared in newspapers and journals and the topic was raised by many debating societies. The London Abolition Committee set up an efficient fund raising activity and produced a number of anti-slavery books and pamphlets. They also arranged for these books to be translated into the languages of the other slave trading powers and a copy of Clarkson’s essay was sent to the Governor of every state in the USA.

Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery designer and manufacturer, joined the committee in its first year. Besides money, he had something every movement needs: a flair for publicity and marketing. His craftsmen designed a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands beseechingly, encircled by the words, ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ Reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cuff links, the image was an instant hit - the first logo designed for a political cause.

The British Government could no longer ignore the anti-slavery issue and hearings on the slave trade were started by the Committee on Trade and Plantations of the Privy Council. This was the first time in any country that the slave trade had been the subject of an official investigation. It enabled abolitionists to put a huge amount of material on the public record and set the scene for the issue to be raised in Parliament.

Josiah Wedgwood’s logo.

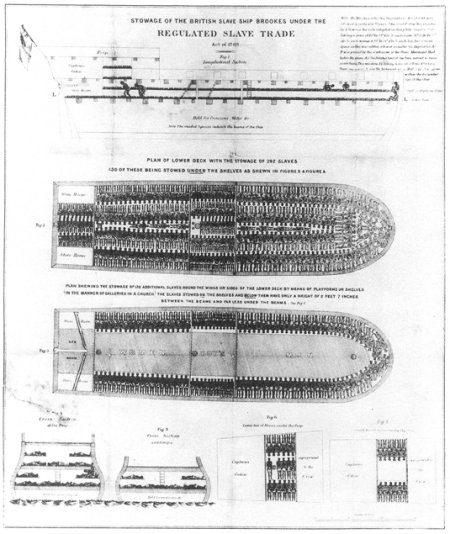

Thomas took charge of organizing the abolition witnesses who appeared at the hearings and he testified himself. When the Privy Council took a break, he rode 1,600 miles in two months scouring the country for more witnesses to the barbarity and cruelty of slavery. He also founded local offshoots of the London Abolition Committee while on the road. The chairman of a new branch he set up in Plymouth soon produced something that immediately spread excitement in anti-slavery circles. It was a diagram showing the top, side, and end views, of a fully loaded slave ship. With the help of other members of the abolition committee, Thomas reworked and expanded the diagram which began appearing in newspapers, magazines, books, pamphlets and as posters. Precise, understated and eloquent in its starkness, it remains one of the most widely reproduced political graphics of all time.

In late April 1789, the Privy Council committee finally issued an 850-page report which laid out the testimony from both sides. Wilberforce had less than three weeks to digest it all before beginning the first parliamentary debate on abolishing the slave trade.

In May 1789 Wilberforce rose in parliament to make his first speech against slavery. He spoke for three and a half hours and Edmund Burke claimed that the speech was "equal to any thing ever heard in modern oratory". Yet the slave interests outmanoeuvred him. They convinced the House that the massive Privy Council report was not enough on such an important subject. Accordingly the House of Commons decided to hold its own hearings.

Soon after the defeat, a crowd in Paris stormed the Bastille and there was the prospect that French antislavery activists would put banning the slave trade on the new regime’s agenda. Thomas went to Paris for discussions with the French abolitionists. He was warmly greeted and two weeks after his arrival the New National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. It proclaimed ‘men are born and remain free’. However, it soon became apparent that opposition to the abolitionists was strong. France had 675,000 slaves on its lucrative Caribbean islands which produced more sugar than the British West Indies. Thomas received death threats and newspapers accused him of being a British spy. Nevertheless he stayed for five months hoping for a breakthrough but then had to return to London to co-ordinate the witnesses for the House of Commons hearings.

Poster of the slave ship 'Brookes'.

These hearings dragged on intermittently until early 1791 and produced 1,700 pages of testimony to add to the 850 pages of the Privy Council testimony. No one could expect even the most sympathetic MP to master this mountain of material so, in the weeks before the next debate on the slave trade began, the abolitionists lead by Thomas worked feverishly to distil some three years of testimony into an account short enough to be given to each MP to read. All this effort was to no avail. After two days of debate in April the House voted two to one against abolishing the slave trade. Despite this defeat the abolitionists still hoped that they were on the edge of victory.

Thomas produced a 160 page summary of the House of Commons testimony and promoted it up and down the country. It became arguably the most widely read abolition literature of all time. In every major town and city throughout the British Isles there were now local abolition committees sending petitions and contributions to London, and receiving, in return the latest books and pamphlets from James Philips' press.

Wilberforce put down another motion for abolition in 1792 and MPs were lobbied intensively by Thomas Clarkson, Sharp, and several other committee members. As the debate drew closer, abolition petitions flooded Parliament as never before. In a few weeks, 519 abolition petitions came from all over England, Scotland, and Wales bearing at least 390,000 names. Only four petitions arrived in favour of the slave trade.

The debate was held in April 1792. The turning point came when the Home Secretary said he was in favour of abolition. He also believed that slaves should be emancipated – but only after much groundwork and education. He thus proposed that the word gradually should be inserted into Wilberforce’s motion to end the slave trade. This amendment was eventually accepted but when the amended bill was sent to the House of Lords it was rejected. The Upper House did not want abolition at all, gradual or otherwise. The abolition movement was stopped in its tracks. The flow of contributions and letters to the London Abolition Committee slowed to a trickle and Wilberforce received a death threat. Within a year the war with France would end the debate on slavery for over a decade.

Thomas’ trip to Paris for discussions with the French abolitionists three years earlier now became an issue. The press branded him a sympathiser of the Revolution and this stoked up hostility to abolition. By now Thomas was suffering from nervous exhaustion and had spent more than half his modest inheritance. By 1794 he felt he had no option but to abandon the cause. Led by Wilberforce his friends raised £1500 to compensate Thomas for his disbursements.

The first phase of the abolition campaign had lasted 5 years during which the faltering steps were also taken to set up a ‘province of freedom’ for former slaves.

In 1785 a number of people wanted to help the estimated ten thousand former slaves in Britain who were living in poverty. Someone who claimed to know West Africa well proposed the establishment of a settlement of emancipated slaves in Sierra Leone – an area which he had visited and knew to have a mild climate and fertile, easily worked soil. Granville Sharpe became involved and the British government promised to supply the necessary transport ships and three months’ worth of supplies.

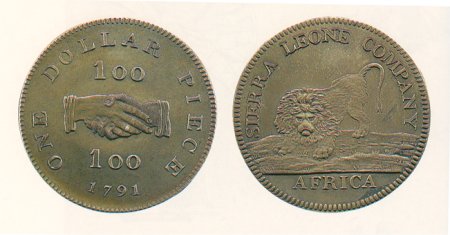

In 1787, a fleet of four ships took 459 settlers to Sierra Leone. They found that conditions there were much harsher than they were told to expect. In the first four months over a quarter of the settlers died. Eventually a private corporation, the Sierra Leone Company, was founded to trade with the colony and issued currency. Several members of London Abolition Committee bought shares in the company but they did not control it.

In 1791, the London Abolition Committee was contacted by Thomas Peters a former slave. He had been sent by other former American slaves who had fled their masters and joined the British forces during the American War of Independence. For this act Britain had promised them freedom. What they received was transport to Nova Scotia, Canada - the nearest British colony. When they heard of the ‘province of freedom’ in Sierra Leone they sent their leader, Thomas Peters, to London to ask the abolitionists for help in getting there. They in turn turned to John Clarkson who had recently been elected onto the Committee. John went to Halifax to recruit settlers for Sierra Leone. Aided by Thomas Peters, he did so with immense success.

In 1792 John led a fleet of fifteen vessels, carrying 1196 settlers, to Sierra Leone. Sixty-five of the Nova Scotians died during the three week voyage and John nearly died himself. Nevertheless the devotion of most of the migrants to John was unbounded: they called him their Moses. He was equally devoted to them and laboured incessantly for their welfare, as superintendent and then as the colony's first governor.

The currency issued by the Sierra Leone Company

Drawing showing the fleet led by John Clarkson

arriving at Sierra Leone in 1792.

The colony survived its very difficult first year because of the close relationship between John and the Nova Scotians. John treated the former slaves as he would treat anyone else. He believed in discipline and good order and achieved this by winning the confidence of those who depended upon him. He respected their intelligence and skills. He understood their aspirations. He was pleased by their religious fervour and frequently attended their services of worship. He said he was ready to ‘sacrifice his life in the defence of the meanest of them’.

His services were at first generally recognized by the directors of the Sierra Leone Company but soon the relationship soured. John insisted on putting the views and interests of the Nova Scotians first, whereas the directors wanted the enterprise to show an early profit. They wanted to demonstrate that they could compete successfully with the slave traders and to bring to Africa, ‘Christianity and the Blessings of Industry and Civilization’.

John returned on leave to England in December 1792. He never returned to Sierra Leone. The directors dismissed him four months later, he having refused to resign. John continued to take a keen if unobtrusive interest in Sierra Leone but never resumed an active part in the anti-slavery movement. But, in 1816, he became one of the principal founders of the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace.

To the end of John’s life, the black colonists demonstrated their attachment to him. Some of their letters survive. The sentiment of these letters was always the same - they wanted Governor Clarkson back with them. The most touching ended, ‘We could say many more things, but after all it will amount to no more than this that we love you and remember your labours of love and compassion towards us with gratitude, and pray that Heaven may always smile on you and yours’.

It is remarkable that a white, British, man could at that time create such a bond of affection and trust between himself and a group of people who had endured years of slavery on the plantations of the American South, who had fought for the British and had then been abandoned by them in bleak Nova Scotia.

Thomas Clarkson’s Period of Recuperation

By the time the campaign to abolish the slave trade was halted by the war with France. Thomas Clarkson was suffering from nervous exhaustion and he abandoned the abolition cause. He also gave up his career in the church and he asked his friends to no longer address him as the Rev. Thomas Clarkson.

He bought a piece of land on the shore of Ullswater in the Lake District and helped local workmen built a small farmhouse there. He was also in love. He had met Catherine Buck, the eldest child of a prosperous yarn maker at Bury St. Edmunds, some years earlier when she had helped with the endless stream of paper work he was producing. She was a vivacious and eloquent woman. They married in 1796 and ten months later their son was born.

Thomas settled down to being a farmer. He grew wheat and oats, barley and clover and kept sheep and bullocks. He and his wife enjoyed a close friendship with their neighbours – the Wordsworths and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They also became friends with Robert Southey and Charles Lamb. During this period Thomas started to write a three volume work on the history and beliefs of the Quakers. He went on to become a prolific author and produced 24 books, including a major biography of William Penn.

The Lakeland idyll came to an end when Catherine Clarkson became ill, apparently with a liver disorder. She sought medical help from one of the country's best doctors and, in 1806 returned to her home town of Bury St Edmunds because the Lakeland climate was thought too severe.

Two years earlier, when the war with France was almost over, Clarkson’s health had recovered and he was busy reviving the campaign against the slave trade. Once again he travelled all over the country to canvass support for the measure and was especially active in persuading MPs to back the parliamentary campaign.

The Final Phase of the Abolition Campaign

During the Parliamentary elections of 1806 the slave trade became a major issue in some constituencies. When Parliament resumed Wilberforce introduced the Slave Trade Abolition Act. By early 1807 the Bill had been passed by both Houses of Parliament and the Bill became law on 25th March – some 20 years after the Abolition Committee was formed. Wilberforce and Clarkson were the two men who deserve most credit for this achievement.

Wilberforce went on to found the African Institution, the aim of which was to improve the conditions of slaves in the West Indies. Deprived of newly imported slaves the plantation owners had no option but to increase the life expectancy of their slaves by treating them less harshly. They also installed improved sugar mill machinery, including a relatively simple safety screen that made it less likely that slaves' hands would get caught between the rollers. As a result of such changes, death rates decreased and birth rates increased.

Thomas Clarkson directed his efforts towards ensuring that the Abolition Act was enforced and in seeking to further the campaign in the rest of Europe. By 1823 it became clear that the trade would not die until slavery itself was abolished and the Anti-Slavery Society was formed. Clarkson once again travelled the length and breadth of the country activating the vast network of sympathetic anti-slavery societies which had been formed. This resulted in 777 petitions being delivered to parliament demanding the gradual emancipation of slaves but they failed to move a grossly unrepresentative Parliament to take action.

When, in 1830, the society finally adopted a policy of immediate emancipation, Clarkson and Wilberforce appeared together for the last time to lend their support. Soon after, events occurred on the other side of the Atlantic that made it harder for Parliament to resist the call to free slaves. Across the West Indies slave riots were breaking out and by 1832 the problem was widespread. An under-secretary at the Colonial office told a House of Commons committee that ‘freeing slaves was the only alternative to a widespread war that might be beyond the government’s military capacity’. A former Jamaican plantation manager and police magistrate testified that the revolts ‘will break out again, and if they do, you will not be able to control them .... I cannot understand how you can expect slaves to be quiet, who are reading the English newspapers’.

Parliament was reformed in 1833 and in its first session there were 3 months of debate before the Slavery Abolition Act was finally passed. The moment was, however, less glorious than expected for those who had worked so long for it. The Act granted compensation of about £37 per slave to their former owners. Worse still, slaves would only be fully liberated after working full time, as ‘apprentices’, for another six years without pay. As a result of pressure on both sides of the ocean, the term of six years was eventually shortened to four.

The real victory came on 1st August 1838, when nearly 800,000 black men, women, and children throughout the British Empire officially became free. Thomas was the only founder member of the London Abolition Committee who was still alive when Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act. Wilberforce had resigned his parliamentary seat in 1825 and died a month before the Act was passed.

Thomas lived for a further thirteen years. Although his eyesight was failing, he continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery, focussing on abolition in the United States. He was the principal speaker at the opening of the anti-slavery convention, held 1840, which sought to extend slavery abolition worldwide.

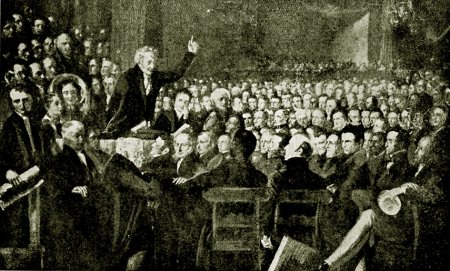

Painting of Thomas Clarkson addressing

the anti-slavery convention in 1840.

The day after his dismissal as governor of Sierra Leone, John married Susanna Lee – a marriage that had been postponed when he left for Nova Scotia. Some time about 1794 became the manager of a huge chalk and lime quarry at Purfleet in Essex. After the company was taken over in 1820 he became a senior partner at Dykes and Samuel Alexander Bank in Woodbridge. This bank, in Church Street, is now Barclays. The family lived in the flat above the bank.

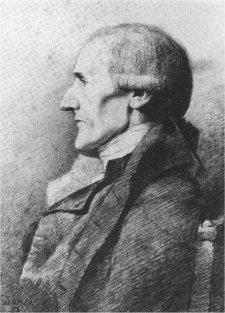

A lithograph showing John Clarkson in circa 1824.

It was produced by the Woodbridge artist

George James Rowe

John was having an abolitionist article read to him when he died of heart disease on 2nd April 1828. His last words were, ‘It is dreadful to think, after my brother and his friends have been labouring for forty years, that such things should still be’. John Clarkson may be forgotten in Britain but copies of the prayer he delivered on his last Sunday in the struggling colony still hang in homes and public places throughout modern Sierra Leone.

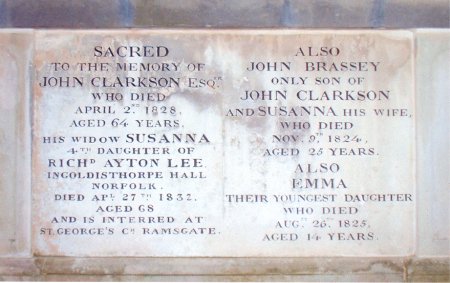

John was buried in St Mary's churchyard along side his son John Bassey and his daughter Emma. Only four of John’s ten children survived him Anna, Mary, Louise and Sophia. Their mother Susanna remained in the flat above the bank for some time before moving to Ramsgate where Anna lived with her husband John Rose, formerly a doctor in Woodbridge. Susanna died in 1832 and was buried in Ramsgate and an inscription was added to her husband's tomb in Woodbridge.

Louisa married Thomas Carthew who was a lawyer and the son of the Rector of St Mary's. She died in 1836, at the age of 26, and is thought to have been the last of the family living in Woodbridge.

Sophia married the Rev Forster Maynard who was curate at St Andrew’s Melton and they subsequently moved to Cambridge. It is through that union that the Clarkson line survives today.

Mary married Tom, the only child of Thomas Clarkson and his wife Catherine.

The inscriptions on the Clarkson tomb at St Mary’s Woodbridge

Thomas Clarkson and his family left Bury in 1816 and moved to Playford Hall which had been let to him by the Earl of Bristol, an abolitionist and admirer who lived in Ickworth. Thomas resumed the farming activities he had enjoyed in the Lake District, although he left the day-to-day work on the 340 acre farm to a manager. Catherine took charge of a school with forty pupils, both boys and girls, held in the chancel of the parish church on Sundays.

Thomas, and Catherine’s son Tom, read law at Trinity College, Cambridge. Tom then set up his own chambers in London and eventually married his cousin Mary, John Clarkson’s third daughter. Tom died in 1837 when he was thrown from his gig in Clerkenwell. By then he had five year old son – yet another Tom – who went with his mother Mary to live with his grandparents at Playford Hall. Tom eventually went to Cambridge University, became a lawyer and inherited Playford Hall. Sadly he led a dissolute life and died without issue in 1872.

Thankfully his grandfather was unaware of these later developments. He died on 26th September 1846. A few weeks earlier he had been visited by William Dillwyn Sim, a relative of William Dillwyn whom came with Anthony Benezet from America eighty years earlier to share their views on slavery with the British Quakers.

Thomas was buried at St Mary's Church, Playford, in a simple family grave. The inscription does not mention his achievements but ten years later some of his surviving friends erected a fifteen-foot obelisk of Aberdeen granite nearby. It bears the simple inscription - Thomas Clarkson the Friend of Slaves.

Alone among the leading abolitionists Thomas was not immediately commemorated in Westminster Abbey, apparently out of consideration for the susceptibilities of his Quaker friends but a large monument to his memory, designed by Gilbert Scott, was erected in 1880 at Wisbech. Finally, in 1996, one hundred and fifty years after his death, a tablet was placed in Westminster Abbey close to Wilberforce’s tomb.

After Thomas died his devoted wife wrote to a Wisbech friend, ‘He was such a grand piece of clay that the persons employed went out of the room backwards as if in the presence of a monarch’.

One of the cards which Thomas Clarkson

gave to his admirers.

A drawing by William Dillwyn Sim showing

Clarkson at Playford Hall.

The graves of the Clarkson family at Playford Church.

The memorial to Thomas Clarkson at Playford Church

and close ups of the two inscriptions on it.

John Clarkson and the African adventure; Ellen Gibson Wilson, The Macmillan Press, 1980

Thomas Clarkson, A Biography; Ellen Gibson Wilson; The Macmillan Press, 1989

Rough Crossing: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution; Simon Schama; BBC Books, 2005.

The Slave Trade, The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440-1870; Hugh Thomas; Picador, 1997

Thomas Clarkson, Friend of Slaves, Robert Malster, Suffolk Review, Autumn 2007.

Last edited 17 Aug 23