Norman Heatley - Pioneer of the Production of Penicillin

Nobel prize winner Alexander Fleming’s name is the one usually linked with the discovery of penicillin. Yet two other scientists, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, also became Nobel laureates for developing penicillin into a useful drug. A Woodbridge man, Norman Heatley, who played at least an equal role, missed out because the rules of the Nobel committee restricted the number elected for an award to three. Heatley was the unsung hero of penicillin production.

It was Heatley's work which enabled sufficient penicillin to be produced for the first clinical trials and which paved the way for the mass production of penicillin by the final stage of the Second Word War.

By June 1941 it was clear than there were insufficient resources to start mass production in England so Healey was sent to the USA. For 12 months he worked there with government’s scientists and a pharmaceutical company to set up a penicillin production facility. He returned to England in July 1942 and by the end of that year the production of penicillin was the second highest priority of the American War Department and another twenty-one companies were making it. Only the development of the atom bomb was considered more important. By D-Day the Allies had sufficient penicillin to treat the troops.

Norman Heatley (1911-2003) was the son of a veterinary surgeon at who had trained at Edinburgh after leaving the family farm in Cheshire. After graduating he taught for two years at the Hollesley Agricultural College which, until 1903, trained people about to set out to the colonies. The buildings are now used for a prison.

When Heatley’s father left the college he established himself as a veterinary surgeon in Woodbridge. Some time later he married Grace Alice Symons, the daughter of a farmer on the Norfolk-Suffolk border, and they moved to Bosworth House, The Thoroughfare. It had a large garden of 2.5 acres in which they eventually built themselves a new house (99, The Thoroughfare) and then sold off Bosworth House with practically no garden.

The Heatley family home (99, The Thoroughfare) is in

the centre of this photograph. In 2008 its gardens

were used for a select housing development.

Norman Heatley was born in 1911. He was an only child who loved sailing on the River Deben in his dinghy. At the age of seven and a half he was sent as a boarder to St Felix School, which had moved from Felixstowe to Ipswich because of the war. A year later he transferred to a boarding school in Folkestone. He graduated in Natural Science at St John’s, Cambridge and stayed on to obtain a PhD for his thesis on ‘The application of micro chemical methods to biological problems’. He was one of the few people who had such skills and was preparing to set up his own commercial chemical analytical service when he was lured to Oxford University by the offer a three year appointment funded by the Medical Research Council.

Norman Heatley. An only child

who loved sailing on the Deben.

The research post at Oxford was offered to Heatley by Howard Florey who, in 1935, was appointed Professor of Pathology at the Dunn School of Pathology. One of his first actions there was to strengthen the biochemistry skills in the department and to that end he hired the flamboyant Ernst Chain, a Jew who had left Germany in 1933. In Oxford, Chain started work on a project that required somebody who was proficient in micro-dissection and micro-micromanipulation and he recommended Heatley for the job.

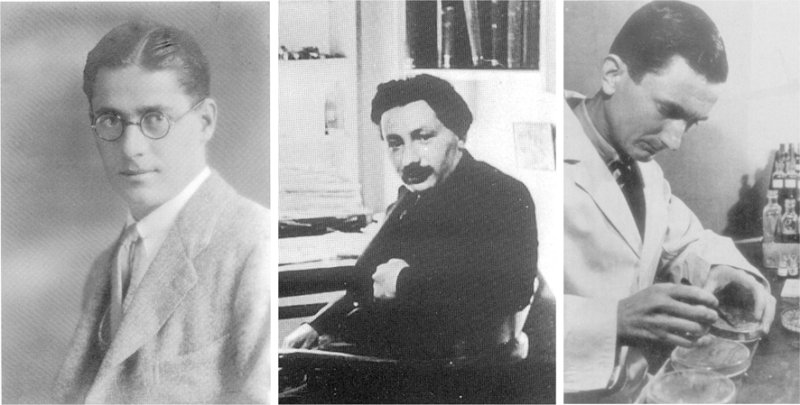

Florey, Chain and Heatley would eventually find a way of demonstrating the therapeutic potential of penicillin. When they came together Florey was aged 37, Chain was 29 and Heatley 24. They were an odd mix. Florey was a blunt speaking Australian who handled people poorly and often failed to read their emotions. Chain was flamboyant and ambitious. Heatley was shy and diffident.

Chain and Heatley worked together on a number of projects and Heatley soon felt that he was doing far more than a normal assistant. He felt that his contribution was being undervalued especially when papers were published.

In 1937 Florey suggested that Chain should study lysozoyme, a substance which Florey had been interested in for eight years. It appeared in duodenal secretions and was known to kill certain bacteria but, as it was ineffective against those causing serious human diseases. So it appeared that it was of no therapeutic interest.

Chain eventually deduced the mechanism by which lysozoyme broke down the cell wall of some bacteria and thereby killed them. He was then keen to understand how other antibacterial substances worked and in 1938 he came across a paper written by Alexander Fleming.

Howard Florey Ernst Chain Norman Heatley

The Orford team which developed penicillin into a useful drug

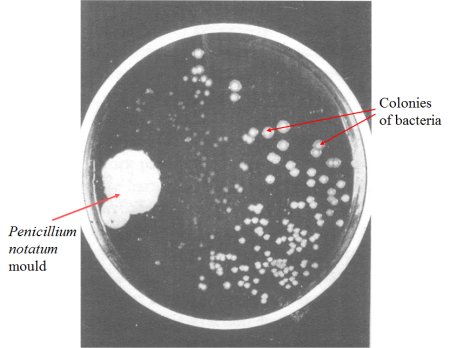

In 1928 Fleming was growing bacteria on a layer of agar in Petri dishes when one of them become accidentally contaminated by the mould penicillium notatum. Fleming noted that the mould was secreting a substance that killed the bacteria. Having made this observation Fleming set about trying to isolate the antibacterial substance. To do so he grew the mould on top of a beef broth rather than on a solid layer of agar.

Fleming then filtered the broth to get something he called mould juice. He then showed that the mould juice was able to kill a wide range of bacteria including some, such as staphylococcus, which were harmful to humans. However, he was unable to extract the antibacterial substance from the mould juice and thereby get something that could be safely used for clinical trials. He also noted that the mould juice, which he later called penicillin, soon lost its potency.

Fleming presented his results at a meeting in 1929 and followed this up with a paper but neither aroused much interest. Three years later, Raistrick, a biochemist colleague of Fleming, showed that the active substance could be removed by mixing acidified mould juice with ether.

The active substance was taken up by the ether and, when the mixture had settled, the ether containing the active substance could be drawn off. Unfortunately, all attempts to separate the active substance from the ether removed its potency against bacteria. So Raistrick was no nearer producing a clinically useful drug. His work was published in 1932 but it failed to excite the scientific community and Fleming lost interest in his discovery.

Fleming noted that the 'penicillium notatum' mould growing on the left of this Petri dish was secreting a substance that killed the bacteria which tried to grow near it

Chain came across Fleming’s papers in 1938 and he persuaded Florey that it would be worth while to start work on the mould Penicillium notatum. Chain was to study the chemistry of the active substance in the mould juice whilst Florey would study its effect on harmful bacteria. In an application for funding Florey called the active substance secreted into the broth penicillin, the name that Fleming had used for the mould juice. Florey would later regret this decision because it enabled Fleming to inflate his role in discovering what would prove to be a wonder drug.

Chain spent several months growing the mould, and trying to find the condition which would produce a sufficient amount of penicillin for biochemical analysis, but he made no progress. Florey then decided to seek the help of Heatley. He had come to the end of his three year grant but the outbreak of war had prevented him taking up a Rockefeller Travelling Fellowship to study in Copenhagen. Florey asked Heatley if he would be prepared to work with Chain on penicillin. Heatley said that, although the work sounded interesting, his lack of regard for Chain would make it impossible for him to continue as his assistant. Florey then suggested that Heatley become his personal assistant and report to him directly. Heatley also said that he was prepared to work with Chain on penicillin, an arrangement that Heatley immediately accepted.

Heatley took over the growing of the mould and started to determine the conditions needed to maximize the amount of penicillin in the mould juice. The work was slowed down by the lack of a simple way to test the antibacterial activity of the mould juice so Heatley devised a new assay method which allowed the antibacterial activity of a sample of mould juice to be measured precisely in what became known as ‘Oxford units’. The technique would later be taken up world wide.

Chain concentrated on trying to extract penicillin from the mould juice. He repeated Raistrick’s experiment but could not find a way of extracting the penicillin from the ether without destroying its antibacterial power. At a meeting between Florey, Chain and Heatley to discuss the problem Heatley came up with the simple idea of adding the mixture of ether and penicillin to water made alkaline and then extracting the water and testing to see if it contained the penicillin. Chain thought the idea was unsound but it intrigued Florey. The meeting ended with Chain saying to Heatley ‘if you think it will work, why don’t you do it yourself? That will surely be the best and quickest way to show you that you are wrong.’

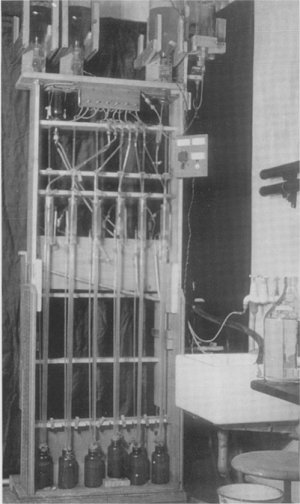

Heatley went away and tried his idea. It worked, and he was eventually able to extract the penicillin in a form that was suitable for clinical trials. Initially he did the extraction manually, but over the next nine months he automated the process. Resources were scarce in wartime Britain but Heatley improvised using what ever was to hand and ended up with a contraption that Heath Robinson would have envied. Nevertheless the basic principles are still used today and there is a replica of Heatley’s apparatus on display at the Science Museum.

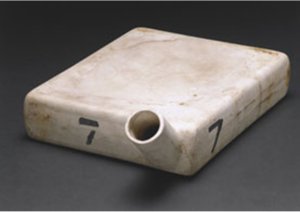

The apparatus which Heatley constructed in 1941 to extract

penicillin from the mould juice. It is now on display at

the Science Museum

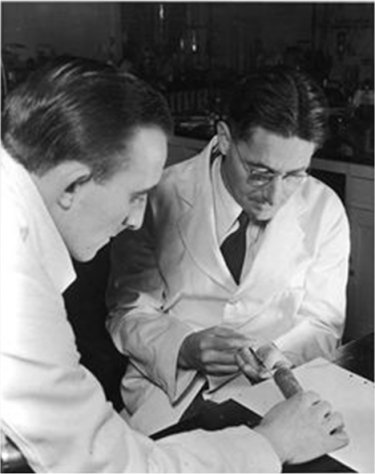

By May 1940 the team was convinced that penicillin could be an important antibacterial drug and the stage was set for a key experiment that proved its remarkable antibiotic power on animals. Eight mice were injected with virulent bacteria and an hour later four of them were injected with dose of penicillin. Heatley monitored the mice overnight and by the morning he could report to Florey that all four of the untreated mice were dead, whilst those injected with penicillin had survived.

The first public announcement of the work was carried in the August 1940 issue of The Lancet. The article entitled ‘Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent’ was signed in alphabetical order by Chain, Florey, Gardner, Heatley, Jennings, Orr-Ewing and Sanders. The team hoped that the publication would stimulate a pharmaceutical company to start making penicillin to test on humans, but this failed and there was no other option but to scale up the production in Oxford.

Florey injecting penicillin into a mouse.

Heatley proposed the use of purpose-built vessels in which to grow the mould. This would allow space to be used much more effectively and thereby increase the amount of penicillin produced. He designed a suitable oblong vessel with a spout. A large number of them were made in ceramic by a manufacturer in Stoke-on-Trent. A production line, the first penicillin factory, was then built inside the Dunn School of Pathology. Seven hundred of Heatley’s vessels were looked after by six technicians, who became known as the ‘penicillin girls’.

By January 1941 enough penicillin was being made to start tests on humans. The dry powder produced at the end of the extraction process was less than one per cent pure, but its effect on patients showed that penicillin had the potential to be miracle cure. Nevertheless there was insufficient penicillin to perform a full clinical trial. Even though Heatley recycled some of the penicillin, by extracting the drug from the urine of patents being treated, one of the patients relapsed and died when the supply of penicillin was exhausted.

To increase production Florey tried to interest British pharmaceutical companies but they were too tied down by wartime commitments. He also approached other academic institutions but they were not prepared to help. Kemble-Bishop, a small company in London’s East End that specialized in fermentation, did offer to produce mould juice but pressure of war work and bombing prevented them from making a contribution until September 1942.

Florey’s final option was to ask the Rockefeller Foundation, which was funding some of the work, to solicit the help of an American pharmaceutical company. The Foundation agreed and paid for Florey and Heatley to travel to the USA to meet with prospective partners. While the arrangements were being made a second paper was prepared for The Lancet. It described in detail the production of penicillin and its effect on the six patients to whom it had been given.

Two ‘Penicillin girls’ tending to Heatley's

700 fermentation vessels.

Heatley’s Fermentation Vessel

Florey and Heatley flew to New York in June 1941 and within two weeks they had been offered the help of the government’s fermentation scientists at the Northern Regional Research Laboratory at Peoria, Illinois. Heatley spent 5 months there and then 7 months working with Merck, the American pharmaceutical company which agreed to produce penicillin. By the time Heatley returned to England in July 1942 the scientists at Peoria had increased the yields of penicillin thirty-fold by using different fermentation techniques and a new strain of mould, discovered growing on a melon. Within a year four other American pharmaceutical companies had started to produce penicillin. Treatment of US soldiers in the Pacific war zone began in April 1943.

By the end of 1942 the production of penicillin was the second highest priority of the American War Department and another twenty-one companies were making it. Only the development of the atom bomb was considered more important. In the first 5 months of 1943 enough penicillin to treat 180 severe cases was produced. In the following 7 months enough to treat 9,225 such cases was manufactured. By D-day, June 6, 1944, there was enough to treat 45,000 cases per month. Pfizer, one of the American companies, was so good at optimising the production process that by the end of 1945 it was making more than half the penicillin in the world and the cost of treating an average case had dropped from $200 in 1943 to only $6.

During Heatley’s absence from Oxford his colleague Gordon Sanders had scaled up the apparatus used to extract the penicillin from the mould juice. Sanders, like Heatley, had to make do by modifying what ever was available. By September 1942 his apparatus was also processing mould juice from Kemball-Bishop, the London fermentation company, and soon after ICI was sending mould juice as well. From 1942 to 1943 some 183 patients were treated and in May 1943 Florey went to North Africa to oversee the use of penicillin on wounded soldiers.

The Therapeutic Research Corporation, a consortium of the five largest British pharmaceutical firms, eventually took up the production of penicillin and shared information with the American companies and the US Office of Science Research and Development.

The scaled up extraction apparatus constructed by Gordon Sanders.

When Florey initiated the collaboration with the Americans he requested that, in return, the UK team would receive 1 kg of penicillin for clinical trials. Only a small fraction of the amount arrived and when the American teams patented their production techniques. There was a loud outcry of indignation in England because the financial rewards for a substance developed in Britain would accrue in the United States. Yet, to be fair, the Americans already had patents on the deep tank fermentation process used in the mass production of penicillin. Moreover, during their work, they identified a number of different types of the drug. The key benefit of the collaboration was that, by D-Day, the Allies had sufficient penicillin to treat all servicemen with infected wounds.

Public Recognition

Florey worked hard within the scientific community, and at government level, to stress the importance of the development of penicillin. He was, however, reticent about talking to the press because wider publicity could raise the hope of thousands of patients who would benefit from penicillin when, in fact, it was likely to be years before there would be enough to give it to them.

Fleming and Almroth Wright, his head of Department at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, had no such qualms. An editorial in the Times calling for an increase in the production of penicillin after the publication of the second paper in The Lancet stimulated Wright to send a letter stressing that Fleming had discovered penicillin and was the first to suggest that the substance might prove to have an important application in medicine. The press flocked to St Mary’s and soon reports were circulating that the Oxford group were simply performing clinical trials on penicillin produced by Fleming at St Mary’s.

Norman Heatley

During the period when the Oxford team were striving to increase their production of penicillin, and to get American and British companies involved, the Fleming band wagon gathered momentum. When Fleming and Florey, along with thirty six others, were knighted in June 1944 it was Fleming’s name alone that made the headlines. When there were rumours that the Nobel Prize Committee was considering making Fleming an award for the discovery of penicillin there was much lobbying in support of the Oxford team. When the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was award in October 1945 it was to Fleming, Florey and Chain for the discovery of penicillin and its curative action. They shared the prize money equally.

There was no award for Heatley who was the first to extract penicillin in a form that allowed its therapeutic potential to be demonstrated. It is a matter of speculation as to what might have happened if the rules of the Nobel Prize had not restricted the maximum number of recipients to three. In 1998 Professor Sir Henry Harris, former Head of the Dunn School of Pathology, was of the opinion that Heatley's work would likely be more appreciated today, in a time when the Nobel Committee places greater value on direct contribution.

Sir Henry went on to say that Heatley ‘was put up for the Royal Society but the rumour was that, because of his diffidence, people regarded him as just a pair of hands for Florey. It was a great injustice.’

When assessing the contributions of the main protagonists in the penicillin story Sir Henry stated ‘Without Fleming, no Florey and Chain; without Florey, no Heatley; without Heatley, no penicillin'.

Heatley was appointed a Nuffield Research Fellow at Lincoln College Oxford in 1948 and received an OBE in 1978. The most significant indication of the value of his work on penicillin came, in 1990, when Oxford University awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in Medicine the first given in its 800-year history - and, in Heatley’s view, ‘an enormous privilege, since I am not medically qualified’.

Heatley was always very modest about his role in the team and never complained about his lack of recognition. He worked with Florey for 30 years and on 19th November 1999 he unveiled the International Historic Chemical Landmark to penicillin at St Mary's Hospital, London, the hospital where Fleming had worked. Four years later Heatley died and obituaries that appeared all recognised his role as the pioneer of the production of penicillin.

The Mould in Dr Florey’s Coat, Eric Lax, A Little Brown Book, 2004.

Penicillin and Luck, Norman Heatley, RCJT Books, 2004.

Tapes made by Norman Heatley about his early life.

Last edited 20 Aug 23