Edwin Lankester -Public Health Reformer

Edwin Lankester (1814-1874), the public health reformer and natural historian, was born in Melton. His parents had been married two months earlier at St Maryís Church, Woodbridge. His father was a builder who died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-seven and was buried in the graveyard of Quay Street Congregational Chapel. His widow was left to bring up their four-year old son Edwin.

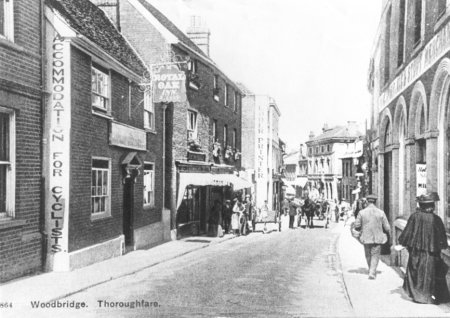

Edwin like his father was a non-conformist so he probably attended the non-conformist British and Foreign School on Castle Street. In 1826, his mother became landlady of the Royal Oak Inn on The Thoroughfare. Edwin, who was then aged 12, left school and was artic1ed for six years to the Woodbridge surgeon Samuel Gissing. He subsequently endured two brief and unsatisfactory assistantships in Hampshire and London before becoming assistant to Thomas Spurgeon of Saffron Walden, Essex, in 1833. Spurgeon took pleasure in furthering the education of his employees and he gave Lankester the use of his library and helped him in his study of the classics. Lankester also became secretary of the local natural history society.

The Royal Oak Inn is on the left of this photograph.

In 1834 friends lent Lankester £300 to support him through a medical course at the newly opened University of London. By 1837 he became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons and licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. At that time surgeons were still considered mere craftsmen while apothecaries were tradesmen. There was a large social gulf between them and physicians who were graduates and thus gentlemen. Oxford and Cambridge were then the only English Universities to offer medical degrees and both had religious tests that would have excluded non-conformists like Edwin.

During his time at the University of London Edwin became president of the college medical society. He then published his first medical paper, and won the Lindley silver medal for botany. This subject, and natural history, remained of interest to Edwin and he pursed them with vigour while at the same time trying to further his medical career.

Through Lindley, the Professor of Botany, Lankester obtained the post of resident medical attendant and science tutor to the family of Charles Wood of Campsall Hall, near Doncaster, where, with his colleague Dr Leonard Schmitz and his two pupils, he was able to broaden his own scientific knowledge and to learn German. In 1839 he travelled to Heidelberg and enrolled at the University there. After six months of study he presented himself for graduation and was awarded the Degree of Doctor of Medicine with Honours.

Edwin Lankester MD, FRS

1814 - 1874

Lankester then settled in London, supporting himself by means of part-time medical appointments at two dispensaries, literary work and popular lectures. From 1842 until at least 1856 he held a part time lectureship at the prestigious Grosvenor Place medical school. He wrote regularly for the Daily News, chiefly on medical reform in support of Thomas Wakley - a London doctor who campaigned for the reform of the medical profession.

In 1823 Thomas Wakley had started publishing The Lancet as a vehicle to attack the autocratic powers of the council that ran the Royal College of Surgeons. He also used it to call for a united profession of apothecaries, physicians and surgeons and a new system of medical qualifications to help improve standards in the medical profession. He also campaigned for medical, rather than legal, coronerships and, when they were introduced, he became coroner for central Middlesex.

Lancasterís primary objective during his early years in London appears to have been to settle down as a doctor in private practice but it was not possible to attract the wealthier citizens unless he could prove himself their social equal by being granted a licence by the Royal College of Physicians.

In 1841 he had been granted a licence to practise in the provinces but his application, five years later, to practise in London was turned down. This rejection resulted in much acrimonious correspondence which was of no avail.

Having been thwarted in his desire to be a London physician, Lankester eventually began to concentrate on science and social medicine. Nevertheless he continued to be an active participant in a number of medical societies and, as a member of the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association, he played an important part in its transformation, in 1856, to the British Medical Association. He was also deeply involved in their struggle with the Royal Colleges for the Medical Reform Bill which was eventually passed in 1858.

Lankester regularly attended, and presented papers at, the meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and, from 1839 to 1864, he was the secretary of the section covering Botany and Zoology. He was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society in 1840 and of the Royal Society in 1845. In that year he married Phebe Pope the daughter of a former mill owner. They had eleven children of whom seven survived to adulthood.

Phebe was a botanist in her own right, producing popular botanical books. After her husband's death Phebe wrote books on health matters.

In 1850 Lankester obtained the chair of Natural Science at New College, London and he held it until 1872. This institution was the result of the fusion of three colleges for the education of Congregationalist ministers. New College London, on Finchley Road, Hampstead, offered a five year liberal education which was also open to students not entering the Ministry. During the 22 years that Lankester held this part time post he was a popular lecturer, contributed to numerous encyclopaedias and reference works and wrote a number of books on popular science. He was as also a skilled microscopist and wrote widely on this subject as well.

Phebe Pope, a botanist, married Lankester in 1845

In 1849 Lankester was elected to the vestry of his parish St James's, Westminster, and was active on a number of its committees when, in 1854, the infamous outbreak of cholera occurred in Broad Street. John Snow, who had published his brilliant theory on the epidemiology of the disease in 1849, quickly traced the outbreak to the local pump, but it was Lankester who enabled him to prove his theory by persuading his reluctant vestry to set up a cholera committee, finance an epidemiological study and publish the results. Lankester also made a microscopical study of water samples and was able to disprove the then prevalent fungoid theory of the cause of cholera.

In 1856, as a result of his work on cholera, Lankester was appointed to be the first medical officer of health for Westminster, a part-time post which he held until his death. He tried to reduce by half the appalling death rate in the slums but he had to fight a parsimonious vestry for adequate funds. He appointed a sanitary inspector to carry out regular inspections of the slum housing, drastically reduced the number of cow-houses and slaughter houses in the basements, and tackled the water supply and the open sewers. His vaccination policy almost halved the incidence of smallpox in the parish, and his leaflets on precautions against cholera were delivered to every household.

Lankester enabled John Snow to prove that this water

pump on Broad Street was the source of cholera.

In 1863 Lankester was appointed coroner for central Middlesex a post previously held by the medical campaigner Thomas Wakley who was mentioned earlier. Lankesterís unorthodox use of the coronership to investigate the social evils causing death was violently opposed by his employers, the Middlesex magistrates, who retaliated by starving him of funds. With the help of the Social Science Association he publicized workhouse deaths, infanticides, and the huge infant death rate, which was often hidden by the incomplete registration of births. He pointed out the need for local mortuaries and for pathologists trained in post-mortem work, and was active in the Coroners' Society. His published annual reports which were eagerly awaited by his colleagues and the public. As always he insisted on the need to educate the public in health maters and continued to publish further popular books.

Lancaster was eventually worn out by ceaseless conflict with a class-conscious, mean, and callous establishment and died at the age of sixty. Some argue that his accomplishments have been unjustly overshadowed by that of his brilliant son Ray.

Edwin Lancaster when he was

coroner for central Middlesex.

Ray Lankester was born in 1847 and was first educated at his home (near Piccadilly Circus) where he met Charles Dickens and eminent scientists such as T H Huxley. He was then sent to a boarding school and, at age eleven, transferred to St Paulís School, London.

When he was sixteen he obtained a scholarship to Downing College, Cambridge. Two years later he moved to Christ Church, Oxford, where, in 1868, he gained first-class honours in Natural Sciences. He was awarded a scholarship to continue his studies at Oxford and a year later was awarded a travelling fellowship which enabled him to study physiology at Leipzig and Vienna, comparative anatomy at Jena and marine zoology at Naples. By 1872 he was a fellow and tutor at Exeter College, Oxford, where he soon made himself unpopular with the authorities by agitating for reforms in the science teaching at the university. He also opposed the dominance of the classics mode of education in the ancient universities.

In 1875 Ray Lankester was appointed to the chair of zoology at University College, London and in the same year was elected to the Royal Society. Sadly his father had died a year earlier so they were not both members of this elite group at the same time.

Ray Lankester was awarded the Societies royal medal in 1885 and the Copley medal in 1913. He was vice-president of the Society in 1883 and 1896 and president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1906. He received many honours from other societies and Universities at home and abroad.

In 1883 Ray Lankester headed a public campaign to raise funds for the creation of a national laboratory for the study of marine zoology. The Marine Biological Association was founded the following year and Ray Lankester took the leading role in raising funds and winning government support. He contributed to the design of the laboratory that was built at Plymouth and he was elected president of the association in 1890.

The following year he accepted the Linacre chair of comparative anatomy at Oxford where he renewed his campaign to reform science teaching at the university. Seven years later he was appointed director of the natural history departments and keeper of zoology at the British Museum, South Kensington. He made effective changes to the museum's displays, and also tried to reform its role as a research institution. This eventually resulted in conflict with the principal librarian and Ray Lankester was forced to retire at the age of sixty in 1907. He was created a KCB soon after.

As well as being the author of many technical papers he also wrote for a more popular readership in a wide range of periodicals. His most important contribution at this level was his weekly article Science from an Easy Chair which began in the Daily Telegraph in 1907.

Ray Lankester saw science as a social and intellectual force that deserved a major role in society and government. In 1916 he chaired a committee to promote the role of science in the war effort and in national life generally. As a young man he had met Karl Marx and was one of the few people who attended Marxís funeral. They both recognised the same evils in society but Lankester thought they could be cured by a science lead meritocracy.

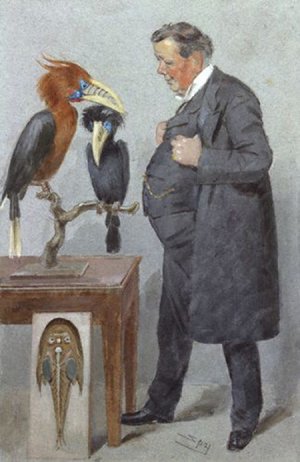

Sir Ray Lankester, FRS

Ray Lankester as depicted in Vanity Fair in 1905

Victorian Values. The life and Times of Dr Edwin Lankester, Mary P English, Biopress Ltd, 1990.

Lankester, Edwin. Mary English, National Dictionary of Biography.

Lankester, Phebe. Anne Shteir, National Dictionary of Biography.

Lankester, Sir (Edwin) Ray. Peter J Bowler, National Dictionary of Biography.

Last edited 18 Aug 23