Alice Driver - Martyr

There was rejoicing in 1553 when Mary became Queen but she soon lost support and there was rejoicing when she died five years later. Mary was uncompromisingly Roman Catholic and was determined to restore that faith throughout her kingdom, undoing the work of her father and brother. In her short reign, which earned her the name 'Bloody Mary', Protestants were burned at the stake for refusing to abandon the new faith and return to the old. Thirty ardent protestants suffered this fate in Suffolk and the number was greater in London, Essex and Kent.

The chief supported of the Roman Catholic religion in the Woodbridge area during the reign of Mary, was Francis Noone of Martlesham Hall, one of the Suffolk Justices. He set in process a series of events leading to two local people being burnt at the stake, in 1558, for their religious beliefs.

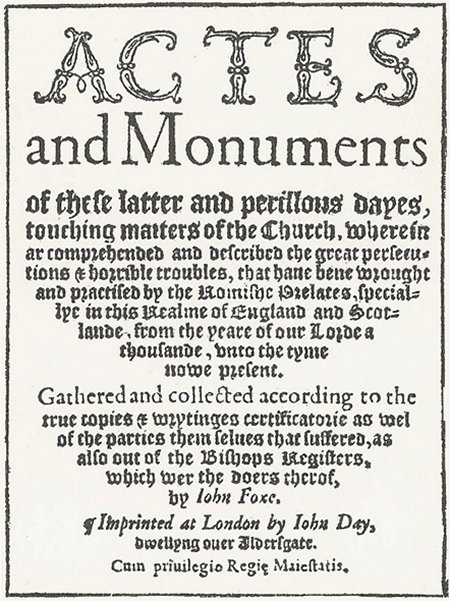

The heart rending details of the story were first given in John Foxe’s book Acts and Monuments which is better known as The Book of Martyrs It is the book which Elizabeth I decreed should be placed in every parish church in order to ferment anti Catholicism. It is thus likely that some of the events described in the account have been exaggerated to create a greater impact.

The title page of John Foxe’s book.

The two local martyrs were the weaver Alexander Gooch, who had moved to Woodbridge from Ufford, and the ploughman’s daughter Alice Driver of Grundisburgh. (Alice was married but little is known about her husband.)

Alexander Gooch (aged 36) fled Woodbridge after speaking out against the Pope and was in hiding at Grundisburgh. There, either by luck or prior arrangement, he met Alice Driver (aged 30) who had learnt to read the English version of the Bible. When Noone arrived with a body of men in search of the Woodbridge fugitive they found Alexander Gooch and Alice Driver hiding in a 'hay-golgh'. They were taken to the gaol at Melton where they remained for a time, before being removed to Bury St Edmunds to attend the Assize of St James’s-tide.

Alice Driver showed more spirit and wit than meekness during her trial at Bury and afterwards at Ipswich. A woman of extraordinary courage, she faced her judges and answered their accusations unmindful of consequences. In days when a word uttered against the Sovereign was promptly met with punishment, she dared to liken Queen Mary, the persecutor, to Jezebel, for which offence Sir Clement Higham immediately ordered that her ears should be cut off.

'Tank you, sir,' was Alice’s response. 'If that is what you need to satisfy your idolatrous beliefs, you shall have my ears. But there are others with ears, and eyes and senses and steady hearts to, who will stand against you in the end'. The mutilation was carried out immediately and she was taken back to Melton Gaol.

Throughout her subsequent trial at Ipswich, and to the very end, a strong personality made itself evident. On entering the judgment hall at Ipswich to be examined by Dr. Spenser, Chancellor of Norwich, she smiled at those who were gathered there. Spencer thus greeted her with the words, 'Why, woman, dost thou laugh us to scorn?' To which she made quick reply, 'I do or no, I might well enough, to see what fools ye be.'

It was useless to try and entrap her into making a confession that should be afterwards used against her, and when the Chancellor asked her why she had been laid in prison she did not help him by the ready answer, 'Wherefore? I think I need not tell you, for ye know it better than I.' To which Spenser, somewhat taken aback, replied, 'No, by my troth woman, I know not why'.

'Then have ye done much wrong', quoth she, 'thus to imprison me, and know no cause why; for I know no evil that I have done, I thank God, and I hope there is no man that can accuse me of any notorious fact that I have done justly'.

Finding it difficult to be even with this clever country-woman, the Chancellor plunged at once into the religious controversy and demanded: 'What sayest thou to the Blessed Sacrament of the altar? Dost thou believe that it is very flesh and blood after the words be spoken of consecration?'

Then followed a long silence. All the multitude gazing at the ploughman's daughter saw her stand with resolute countenance and lips sealed.

This was too much for 'a great chuff-headed priest who stood by'. Probably thinking that either she could find no answer, or if hurried into speech, would commit herself at once, he urged her to answer the Chancellor. But it would have been well for him if he had not interfered, for, looking at him austerely, she administered this rebuke: 'Why, priest, I came not to talk with thee, but I came to talk with thy master, but if thou wilt I shall talk with thee, command thy master to hold his peace'.

Perhaps this unexpected rejoinder provoked the bystanders to mirth. At any rate the chronicler tells us that 'with that the priest put his nose in his cap and spake never a word again'.

But it was not for lack of words that Alice Driver held her peace. She only wished to emphasize her astonishment that such a question could be asked, and when the Chancellor again pressed her for a reply, she calmly said, 'Sir, pardon me though I make no answer, for I cannot tell what you mean thereby, for in all my life I never heard nor read of any such Sacrament in all the Scripture'.

'Why, what Scriptures have you read?' asked Spenser. 'I have (I thank God) read God's Book', replied the 'woman.

To which the Chancellor quickly responded. 'Why, what manner of book is that you call God's Book?'

'It is the Old and New Testament. What call you it?' questioned Alice in her turn.

Spenser being obliged to admit that this indeed was God's Word, she then continued to interrogate her judge, and to such purpose that the words of this simple woman may with profit be recorded.

'That same book have I read throughout', she said, 'but yet never could find any such Sacrament there; and for that cause I cannot make answer to that thing I know not. Notwithstanding for all, I will grant you a Sacrament, called the Lord's Supper, and therefore seeing I have granted you a Sacrament, I pray you show me what a Sacrament is'.

'It is a sign', replied Spenser, whereupon Dr. Gascoigne, who was standing by, 'confirmed the same, that it was a sign of a holy thing'.

'You have said the truth, sir', said she, 'it is a sign indeed, and I must needs grant it; and therefore seeing it is a sign, it cannot be the thing signified also. Thus far we agree, for I have granted you your own saying.'

It is impossible in this short account to give further particulars of the trial, but we may well regard with astonishment the wisdom displayed by this unlettered daughter of the people. For herself, she rightly attributed the readiness of her replies to the direct intervention of the Holy Spirit, and we cannot do better than to give her own words uttered just before the sentence of condemnation was passed upon her.

There had been a short pause in the proceedings, for one by one her adversaries had been put to shame by the ready wit that met every question directed against her, and now she spoke for the last time. 'Have you any more to say? God be honoured. You be not able to resist the Spirit of God in me, a poor woman. I am an honest poor man's daughter, never brought up in the University, as you have been, but I have driven the plough before my father many a time (I thank God); yet, notwithstanding, in the defence of God's truth, and in the cause of my Master Christ, by His grace I will set my foot against the foot of any of you all, in the maintenance and defence of the same, and if I had a thousand lives, they should go for payment thereof.'

On the 4th of November, 1558, at seven o'clock in the morning, Alexander Gooch, of Woodbridge, and Alice Driver, of Grundisburgh, were taken to the Cornhill, Ipswich, where the stake was set up for their burning.

Amongst the multitudes that thronged the place even at that early hour, were many whose sympathies were with the victims, and demonstrations of affection and pity helped to encourage them in their last hour of agony. Kneeling upon a broom faggot, they offered their simple prayers to God, and sang, Psalms together till one of the bailiffs, Richard Smart by name, roughly bade them "have done”.

In vain they appealed for further time in which to prepare for the solemn hour. Doubtless fearing the effects of such scenes upon the multitude, Sir Henry Dowell, the Sheriff, thereupon commanded that they should be tied to the stake. As the heavy iron chain was fastened about Alice Driver's neck, once more the heroic spirit of the woman made itself evident, and her last recorded words are eminently characteristic:-'Oh!' she said, 'Here is a goodly neckerchief; blessed be God for it'. Then a light was set to the twigs.

Two weeks later Queen Mary died and the burnings ended.

Other Sources

Acts and Monuments, Foxe

Bygone Woodbridge, V Redstone

Colourful Characters from East Anglia, H Mills West

Tudor and Stuart Suffolk , Gordon Blackwell, Carnegie Publishing.

Last edited 21 Aug 23