Raymond 0 Faulkner - Egyptologist

Dr Raymond Faulkner and his wife moved to Woodbridge soon after he was appointed, in 1954, as part-time Lecturer in Egyptian Language at University College London. They lived in 1 Quayside, a timber framed house across the road from the station. Raymond Faulkner was still living there when he died in 1982. A photograph of the house in 2017 is shown below. It is the white building in the centre of the photograph. His obituary in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology is reproduced in the next section.

Raymond Faulkner lived in the white building in the centre of this photograph. It is on Quayside and abuts Quay Street.

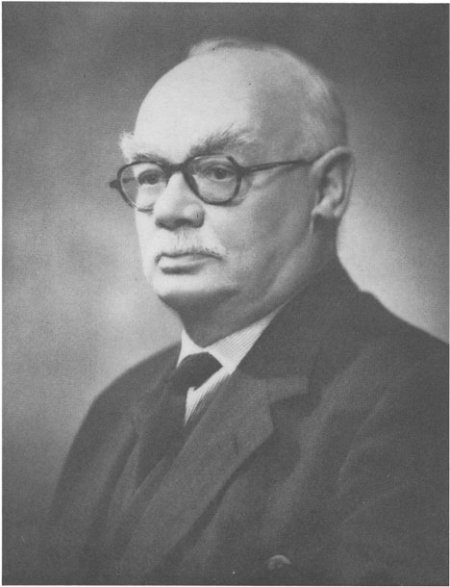

RAYMOND FAULKNER

1892-1982

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 69 (1983), pp. 141-144.

Dr Raymond Faulkner died at Woodbridge, Suffolk, in March, 1982, at the age of 88. He was an enthusiast for Egyptology who spent all the energies of his maturity and old age in devoted and selfless service to his subject, and was loved and honoured by all who knew him.

Faulkner's career divides itself into four parts. At the age of 18 he entered the Civil Service, but volunteered for the army at the outbreak of the First World War. After fighting in the trenches throughout the early campaigns of the war, he was severely wounded and invalided out. He re-joined the Civil Service in 1916, but his intellectual interests had broadened, and a passionate interest in Egyptology caused him to enrol at University College London to study hieroglyphs in his spare time under Dr Margaret Murray. To her he owed the life-long interest in Egyptian funerary texts shown in his first two articles on 'The "Cannibal Hymn" from the Pyramid Texts' and 'The God Setekh in the Pyramid Texts', published in 1924 and 1925.

In 1926, Sir Alan Gardiner, then at the peak of his scholarly powers, invited Faulkner to become his full-time Egyptology assistant. This revolutionized his life, and allowed him henceforth to devote himself to the studies he loved. Naturally, during the long years of his happy collaboration with Gardiner from 1926 to 1954, it was to Gardiner's great text publications that Faulkner principally contributed. To his patience, skill, and care much detailed work was due, in particular the autography of the hieroglyphic texts, the commentaries, and the indexes, the most notable examples of which are surely Ancient Egyptian Onomastica and The Wilbour Papyrus Vol. iv. Index. Faulkner insisted that he learnt almost everything from Gardiner and was always faithful to his principles. At the same time Gardiner encouraged his independent publications, of which perhaps the most important was his edition of the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus; in some of these he expressed views contrary to Gardiner's own, as in 'The Battle of Megiddo'.

In 1954 he was appointed to a part-time Lectureship in Egyptian Language at University College London, and soon afterwards he and his wife, whom he had married in 1937, moved to Woodbridge. He taught at University College for thirteen years, and every student who came under him benefited not only from his strict insistence on the niceties of Egyptian morphology and syntax and the importance of a good hieroglyphic hand-a field in which he was himself paramount - but also from his constant and enthusiastic search for new interpretations. Every reading of a hieroglyphic text, however well known, was for Faulkner an adventure; it was rare for him not to produce some new interpretation. Equally he appreciated initiative by students, whose ideas always received the most generous encouragement and criticism. It was during these years of teaching that Faulkner realized the outstanding need felt by elementary students of hieroglyphs for a reliable, portable, yet scholarly short dictionary. Putting aside his long-cherished projects, he produced from his own slips A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, autographed by himself and published in 1962. Undoubtedly, this was Faulkner's outstanding service to Egyptology students-and not only students; it seems doubtful whether any other Egyptology work, except perhaps Gardiner's Egyptian Grammar, is so widely used.

Faulkner's retirement in 1967 at the age of 73 was the prelude to the most productive period of his career. His favourite project of producing a new, standard English translation of The Pyramid Texts to set beside Sethe's monumental Pyramidentexte had already, it is true, been in hand for many years. But the leisure given him by retirement allowed him to complete the proof-reading of this monumental work, which was published by Oxford University Press in I969 with a generous subvention from Sir Alan Gardiner's Trust.

Faulkner had already started on a new project, to provide a pioneer English translation of Professor Adriaan de Buck's great edition of the Coffin Texts. Despite a heart condition from which he had long suffered and some failure of eyesight, Faulkner worked steadily at his appointed task, never accepting that he had the final answer, constantly open to criticism and suggestions, but realistic in his judgement of when to leave a problem unsolved. He also contributed an important chapter to the Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. II (Ch. XXIII: Egypt: From the Inception of the Nineteenth Dynasty to the Death of Ramesses III).

Despite his involvement with this work, he nevertheless found time to complete and edit S. R. K. Glanville's Wooden Model Boats.

Throughout his career he had built up his own translations of standard Egyptian literary texts, some of which he had published. This led to his being asked by Professor W. K. Simpson to collaborate with himself and Professor E. F. Wente in an up-to-date anthology of stories, instructions, and poetry entitled The Literature of Ancient Egypt, published by Yale University Press in 1972. This compact volume formed a much-needed replacement for A. Erman's The Literature of the Ancient Egyptians (1927), and, though now rivalled by Professor M. Lichtheim's three excellent volumes, is still one of the first works to put in the hands of Egyptology enthusiasts.

Faulkner was also asked to produce for the members of the Limited Editions Club, New York, a translation of The Book of the Dead from papyri in the British Museum. This was issued in 1972; it was based principally on the Papyrus of Ani and included a handsome reproduction of that papyrus. With all these works in hand, it is hardly surprising that Faulkner's translation of the Coffin Texts took time. To his disappointment the Oxford University Press found themselves unwilling to publish it, but Messrs. Aris and Phillips, then at the beginning of their career, gallantly accepted the challenge, and produced an edition to form, as far as possible, a companion to The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Vol. I was published in 1973, Vol. II in 1977, and Vol. III in 1978. Immediately after its completion, Faulkner settled down to the production of a complete glossary of the Coffin Texts. In his last years he was only able to work an hour or so a day, but he continued steadily and his work was nearing completion when he died. It is hoped that it may yet be published.

Faulkner's translations of Egyptian funerary books may be criticized on various grounds. He did not provide the extensive commentaries necessary for the understanding of these difficult spells and their extensive mythological background; his brief notes are mainly confined to textual matters. Out of instinctive loyalty to Gardiner, as well as his own bent, Faulkner did not accept all of the advances that have been made in Egyptian grammar over the last fifty years, notably those pioneered by Professor H. J. Polotsky. He also did not hesitate to conflate texts where he thought it would yield a more intelligible sense. Many of his detailed interpretations will, therefore, no doubt, be challenged or improved in forthcoming works. But, in judging Faulkner's work, it must be remembered that this was what he wished to provoke, and that his prime intention was to provide a compact, yet reliable version in English for those scholars and students, whether of history of religion, anthropology, or oriental studies, who had not sufficient command of Ancient Egyptian to tackle the originals. These users, as well as Egyptology students, will always be deeply grateful to Faulkner, especially for his pioneering work on the Coffin Texts. Faulkner's distinguished services to scholarship were recognized by his election as a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1950, as a Fellow of University College London in 1958, and by the award of the Degree of D.Lit. by London University in 1960.

None of this catalogue of achievement conveys anything of the charm of Faulkner's character and personality. Short and stockily built, his moustache, bushy eyebrows, and firm countenance gave a decidedly military impression, enhanced by a staccato manner of speech not unlike the rattle of small-arms fire. He had a great dignity and sense of fitness, and a sternly disciplined attitude to serious aspects of life and of scholarship. These attributes sometimes overawed students in their early classes with him. All, however, discovered eventually the great good-humour, gentleness, and goodwill to all that were the hallmarks of his character. In his work and in his life Faulkner set himself to serve. Justly proud of his achievement, he was nevertheless innately an extremely modest man, content to live in relative obscurity on exiguous means, so long as he could serve learning and forward the cause of Egyptology. Himself initially an amateur enthusiast, he had a real understanding of their needs, shown clearly in his work. Above all, he maintained a balance in his interests, which included astronomy and philately, and in his life, where he greatly enjoyed social contact of an intimate, wholly English variety. This breadth of interest informs all his work, as does his wide experience of sailing, soldiering, riding, and the flavour of his personality Faulkner belonged very much with those great amateur scholars of the generation preceding his own-Sir Alan Gardiner, Walter Ewing Crum, and Sir Herbert Thompson-though his circumstances in life were in stark contrast to theirs. Ever honourable, gentlemanly, and generous, he preserved a mannerly reticence that always masked the sorrows of his life, such as his wife's long illness; to the world, he presented philosophic contentment with his own brand of twinkling wit, outward symbols of a stalwart heart. In Raymond Faulkner all who knew him have lost an admired colleague and a warm friend.

Last Edited 17 Aug 23