Local Governance

The End of the Workhouses and the Creation of the Welfare State

The 1906 general election ushered in a Liberal Government that passed laws to protect people from the causes and the effects of poverty. The National Insurance Act of 1911 and Unemployment Insurance Act of 1920 provided sickness benefits and unemployment pay for certain categories of workers. This eased the burden on the poor rates but there were still many people who had no option but to seek help from a Poor Law Union.

The Local Government Act of 1929 abolished the Poor Law Unions and transferred the responsibility for public assistance to county councils and county boroughs. Care for the sick or infirm paupers was dispersed to a variety of agencies. Provision for the able-bodied poor was transferred to Public Assistance Committees and workhouses became public assistance institutions. From this point on the costs of caring for the poor of a county were spread uniformly across all the ratepayers in that county.

The Unemployment Assistance Board was set up in 1934 to deal with those not covered by the earlier 1911 National Insurance Act passed by the Liberals and, by 1937, the able-bodied poor had been absorbed into this scheme.

The depression from 1929 to 1939 resulted in the expenditure on unemployment benefit becoming unsustainable and it had to be reduced by 10%. It was the terrible poverty and unemployment during this decade which persuaded many reformers that an insurance scheme was needed to cover the whole population and which would provide all citizens with security from want “from the cradle to the grave”. The result was The National Health Service Act of 1946 and the National Assistance Act of 1948. These Acts, sometimes referred to as the ‘Social Security Acts’ made adequate provision for all the groups which had previously relied on the Poor Law.

Organizing Defences against Fire

The churchwardens’ accounts for 1626 record the purchase of 16 leather buckets. In a schedule of “church goods” for the same period there is a mention of “two fire hooks and a long ladder”. In the eighteenth century two manual engines, the “Great Engine” and the Little Engine”, were obtained and stored at the base of the church tower under the care of the Sexton, John Fosdike. In 1817 the base of the tower was included in the main body of the church and the engines, pumps, buckets and ladders were transferred to the then open ground floor of the Shire Hall.

In about 1847 one of the old fire engines was sold and replaced. In 1853 several of the prominent inhabitants resolved to build an engine station by public subscription. This modest building was subsequently erected in Cumberland Street and a brigade was formed of 10 “working men” from the town.

In 1873 there was public concern about the way a large farm fire had been handled and, as a result, a new brigade the “Woodbridge Volunteer Fire Brigade” was formed. The new brigade still depended on volunteers but this time they were drawn from tradesmen of the town. Each of them was provided with a uniform, helmet, and payment for call out and practices.

Link to other photographs of the Fire Engine Station and the Fire Engines.

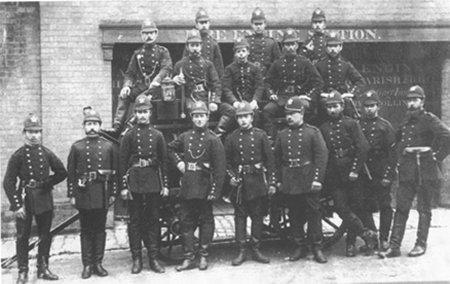

The Woodbridge Fire Brigade outside the Fire Station on Cumberland Street. When the Urban District Council was formed in 1894 it took over responsibility for the town’s Fire Service. The Brigade was still summoned by jangling the Church Bells – two jangles for a fire in country, three jangles for one in the town.

.

Public Health

There was almost a threefold increase in the population of England during the period 1750 to 1850. Most of the increase was in urban centres and the health of those living in them became progressively worse. It was left to the local communities to find the best ways of minimising the problem and to raise the necessary funds. In Woodbridge, for example, two "Pest Houses" were built near the parish boundary on the Grundisburgh Road in 1755. When an inhabitant of the town showed signs of small pox, or another contagious disease, they were removed to these houses. The money needed to build them was raised by asking townspeople to contribute what they could afford.

Edwin Chadwick, one of the architects of the 1834 Poor Law Act realized that a significant percentage of the poor relief was given to the families of men who had died from infectious diseases. He thus concluded that money spent on improving public health would be cost effective as it would save money in the long term. The Health of the Towns Act of 1846 and the 1848 Public Health Act led to the formation of Local Boards to deal with sanitation, water supply, public parks, baths, fire hazards and to appoint a medical officer. Many of the larger parishes were already addressing some of these services so the Acts merely formalized their efforts. As was the case with poor relief, the costs of providing these services was to be raised by taxes set and collected locally.

There were Local Boards of Health for large urban centres and for populous parishes such as Woodbridge. Members of these boards were elected by owners of property and by rate payers. Parishes in rural areas were encouraged to join together and create Rural Local Boards to perform the functions required.

The one remaining Pest House is now a private residence.